The Matrix Reloaded – our guide to the risk assessment matrix

The humble Risk Assessment Matrix (RAM) comes in for a lot of criticism. Whilst some of this may be justified, some arises more from a misunderstanding of the purpose and intended use of the RAM. There are strong views expressed on both sides of the argument (see Ref. 1 example). Here, we provide practical guidance on some of the more common issues.

WHAT IS A RAM?

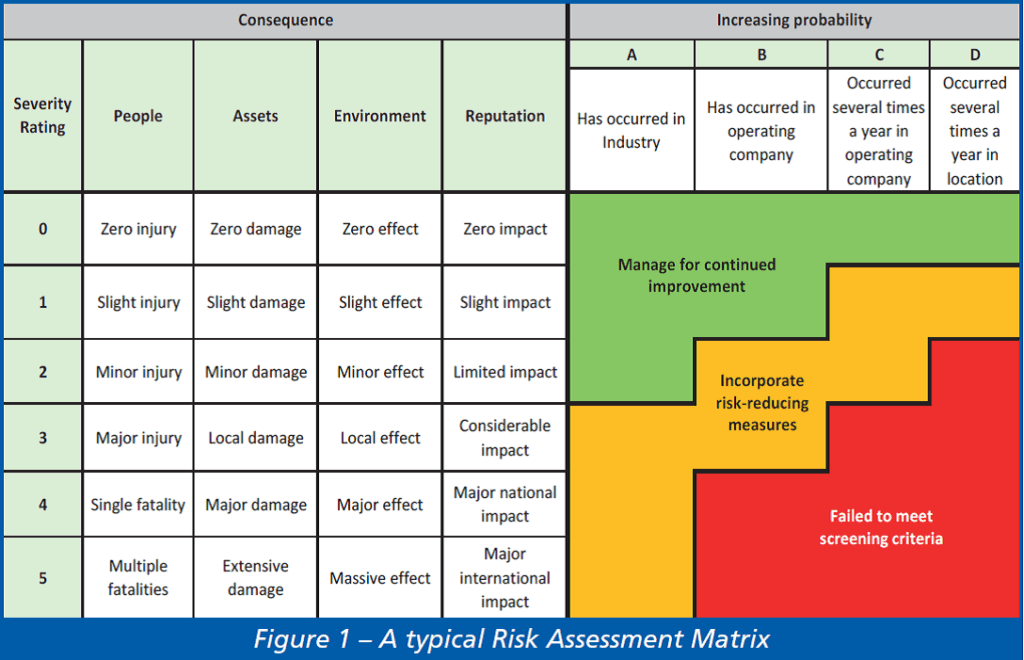

A RAM is a matrix that is used during risk assessment to define the various levels of risk as the combination of probability and consequence categories. Figure 1, derived from ISO 17776, shows a typical example. A RAM is a simple tool intended to increase visibility of risks and assist decision-making.

KEEP IN MIND THE PURPOSE

The key benefit of a RAM is to give a rapid and consistent appreciation of the risk levels and, hopefully, to encourage a discussion and common understanding of how severe hazardous scenarios can be and how often they could occur. The RAM risk level scores are there to help make an informed decision as to the acceptability of that risk. The actual cell chosen should not be too critical, and if the decision-making process is indelibly tied to the exact position on the RAM, then a more detailed assessment method would be appropriate.

DOES IT MATTER?

RAMs come in many different shapes and sizes, ranging from 3×3 to 10×10. Too small a RAM may not give sufficient resolution, whilst too large may take longer to use and it is questionable whether this level of granularity is really needed. The most common tend towards the 6×4, 5×5 or 6×6 type.

However, don’t assume that because there are only two axes and 25 cells, that everyone will use the RAM in the same way. What is important is consistency and that that there is clear guidance on its use.

UNMITIGATED AND RESIDUAL RISK

One contentious area that commonly results in poor use of the RAM is in assessing residual risk. Residual risk, when combined with the initial unmitigated risk scores, has the advantage of showing a moving score on the RAM. Unfortunately this allows some people to claim, falsely, that this proves risk levels have been reduced as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP).

Part of the problem lies with the difficulty in determining the unmitigated risk. This answers the question, “If nothing works, how bad could it be?” The acceptance of residual risk then relies on assessing whether “given the controls we have in place, is that good enough?” But it’s not always practical to completely discount controls in gauging the unmitigated risk. You might argue that the unmitigated risk of driving a car should consider an unlicensed driver in a car with no mechanical integrity on unmade roads, but is this realistic? But if we allow for a licensed driver in a roadworthy car on a freeway, why then should we not claim the seat belts and airbags as well? The solution to this conundrum is to define at the outset precisely what is meant by unmitigated and residual risk.

THAT’S THE POINT

A RAM gives point risk scores for individual scenarios. Whilst it is often useful to prepare heat maps showing the relative distribution of events across the RAM, this isn’t the same as determining a cumulative risk score. Individual events may affect different groups of people, and may also lead to multiple consequences occurring simultaneously.

ONE SIZE FITS ALL…OR NOT?

Should an entire company employ a single common RAM, or should each department have its own specific one? The former allows for a consistent approach but can lead to increased RAM size to handle risk assessments ranging from workplace hazards to events threatening the corporation. The latter allows for simple, highly targeted assessments, but managing consistency across an organisation becomes more difficult.

CONCLUSION

The RAM provides a simple, well-used approach to risk assessment with considerable benefits in promoting discussion and achieving a common understanding of the risks. Despite its simplicity it is still open to abuse both unconsciously (“It’s simple so I don;t have to think very hard”) and consciously (“I can use this to my advantage”) from people ascribing greater accuracy than the matrix can achieve or using it to uphold a decision that has already been made, rather than using the ALARP process.

References

1. Cox, L.A., What’s wrong with risk matrices? 2008.

2. Talbot, J., What’s right with risk matrices?

This article first appeared in RISKworld issue 30