On Reflection: Advances in risk and safety management over the last 20 years

As we celebrate Risktec’s 20th birthday, we reflect on some of the main advances in risk and safety management we’ve seen over the first two decades of the 21st century.

SOCIETAL EXPECTATIONS

There is no doubt that society’s increasing mistrust of high hazard sectors has been the major driver of advances in risk and safety management over the last 20 years. Today, there is more legislation and stricter regulatory enforcement across more industries in more countries than ever before.

Unfortunately, society’s mistrust is well-founded. In the ‘noughties’ we saw major accidents such as the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster (2003), Texas City refinery explosion (2005) and Buncefield oil storage explosion (2005). In the ‘tens’ we had the Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout (2010), Fukushima nuclear meltdown (2011) and Brumadinho dam failure (2019) amongst others. All highlighted to a global audience the adverse human, environmental and financial costs of low-frequency, high-impact failures of complex technological systems.

Subsequent root cause investigations have highlighted more than ever the importance of taking a complete approach to risk management. Twenty years ago managing risk was more the domain of risk and safety engineers engaged in the technical design phase of a project, whereas today it is also as much about leadership commitment, structured management systems and a reliable culture which engages the workforce.

QUANTITATIVE RISK ASSESSMENT

With computing power around a thousand times greater than 20 years ago, it is no surprise that it is much quicker and easier today to run complex analyses such as CFD explosion modelling or multi-site QRAs. Industry standard software has more advanced algorithms and functionality that better aligns with historical and experimental data. Furthermore, developing bespoke software has never been so easy – today it is more about the plumbing together of open source routines than the time consuming, line-by-line coding of 2000. And Excel is ever more versatile and powerful – what used to take a month can be done in a week.

We are much better positioned with data too. Long-standing databases have 20 years of additional data points and the internet has made finding and accessing data sources so much easier and cheaper.

All of this has helped to reduce (or better quantify) the uncertainty in results and thus aid more informed decision-making. But there are pitfalls to avoid, for instance: believing the numbers out-of-the-box rather than engaging in an experienced-based challenge of the results; using easy to find, poor quality datasets rather than peer reviewed, authoritative sources; and shaving the margin of safety in a design to a level that is not justified by the residual uncertainty.

QUALITATIVE RISK ASSESSMENT

The most ubiquitous qualitative methods such as HAZOP and FMEA are fundamentally no different today than they were 20 years ago. But recording and reporting software is certainly much better and there is a stronger working relationship between HAZOP and LOPA.

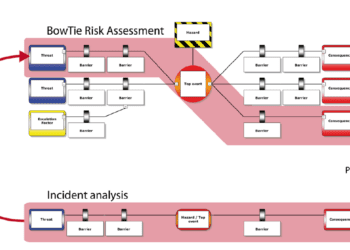

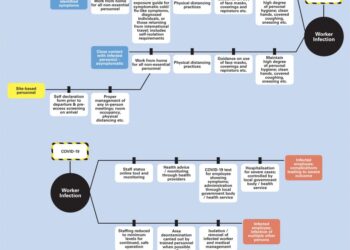

One tool that was barely used 20 years ago and is now widely accepted and applied worldwide is bowtie analysis. Its popularity is probably due to the output being readily understandable by both risk specialists and non-specialists.

Human factors techniques such as safety-critical task analysis (SCTA) have grown in prominence in recent years, along with the increasing recognition of the importance of preventing human errors and deliberate violations.

Risk matrices were around 20 years ago, albeit mainly in the hands of risk practitioners. Today most corporations will have one or more risk matrices that are calibrated to their activities and are widely used for all kinds of risk assessments, from workplace tasks to facility operations to company survival.

MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

We’ve seen substantial progress in transitioning from an ad-hoc mosaic of policies and procedures to structured systems for the consistent and systematic management of different types of risk, all based on the requirements of new ISO standards.

In fact, there’s been a deluge of standards since the 14001 environmental standard in 1996, and many organisations have been formally certified against them. For example: 27001 for information security in 2005; 18001 for safety in 2007 (now 45001); 31000 for all risks in 2009; 22301 for business continuity in 2012; and, most recently, 27914 for geological storage of carbon dioxide in 2019. Furthermore, all of these risk areas are supported by more detailed technical guidance and approved codes of practice.

Many companies have also worked hard to integrate some of these systems to avoid operating in silos, especially in health and safety and environmental protection, although there is undoubtedly much more still to be done.

THE HUMAN FACTOR

Most organisations in the high hazard industries are dominated by technical people, such as engineers and scientists, so it is hardly surprising we’ve seen a great deal of progress in technical analysis and structured management processes. Fortunately, we have also seen progress in addressing the importance of organisational factors and people in preventing major accidents.

The hearts and minds safety culture model, for instance, introduced around 2000, provides a framework for organisations to assess their current culture and move up an evolutionary ladder. Over the past two decades we’ve seen the journey of many organisations who began stepping up the ladder. Some started at the reactive stage where something was only done after there was an incident, and many have reached the calculative stage where systems are in place to manage all hazards. Others have progressed further, to the proactive stage where values, leadership and workforce involvement drive safety improvements. Perhaps a few have maintained or reached the generative or high-reliability organisation stage, where there is a collective mindfulness to prevent all failures.

Clearly, not least because organisations are always changing, enhancing safety culture is a never ending process, but arguably provides the greatest opportunity for improvement in safety performance in future decades.

CONCLUSION

Risk and safety management has certainly matured over the past 20 years and gained a higher profile in organisations operating within high hazard industries. Technical risk assessments are more advanced, structured management systems have been put in place, and organisational, cultural and behavioural factors are being addressed to some extent.

Of course, 2021 doesn’t mark the peak of performance. The risk and safety profession can look forward to another 20 years of advancement, helping all facets of risk and safety management, while facing the many technological and societal challenges that lie ahead.

This article first appeared in RISKworld 40, issued November 2021.