Blown away – the end of Chapelcross cooling towers

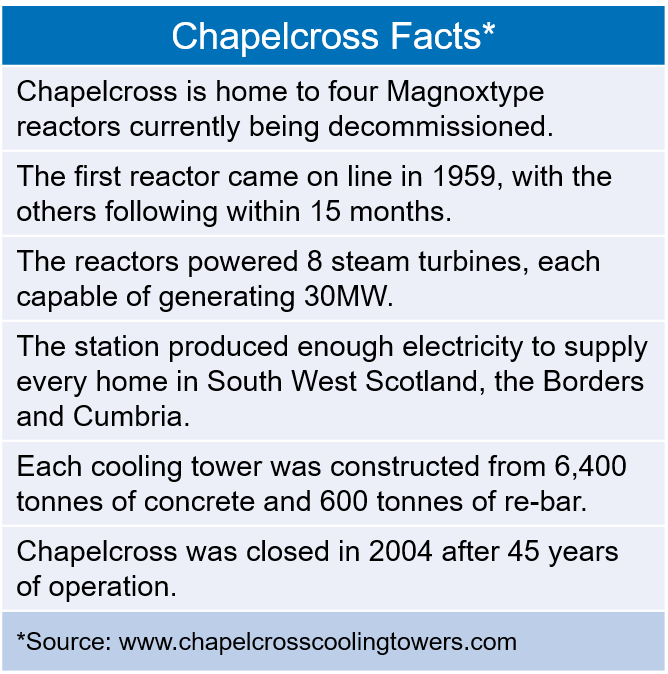

At 9am on Sunday 21st May 2007, the quiet of the Solway Firth was awakened by the sound of approximately 15,000 explosive charges detonating in staggered phases. In just ten seconds, the four 90 metre high cooling towers, which had dominated the skyline for almost 50 years, were levelled, leaving an estimated 28,000 tonnes of rubble. As well as marking the end of the Chapelcross power station [see Table1], this graphic demolition belied a wealth of necessary technical assessment.

A BALANCE OF RISK

Cooling tower design employs the hourglass shape to reduce incident wind loadings and minimise tensile forces. In the UK, however, a number of factors meant that the dynamic effects of winds were underestimated, culminating in the collapse of three cooling towers within an hour at the Ferrybridge coal-fired power station in 1965. In a separate incident in 1973, a cooling tower collapsed at the Ardeer Nylon Works in Ayrshire, largely due to geometric imperfections.

Shortly after, a degree of structural asymmetry was uncovered in one of the cooling towers at Chapelcross. As a result, the Chapelcross cooling towers were reinforced in 1977 by the addition of an external layer of reinforced concrete. However, even after these strengthening works, the cooling towers fell short of modern design codes. In planning the decommissioning of Chapelcross, the decision was therefore taken to demolish the cooling towers as soon as practicable to minimise the risk to nearby reactor buildings associated with inadvertent collapse.

BIG BANG IS BEST

After a detailed investigation, it was concluded that the best practicable means of demolishing the cooling towers was by rapid implosion, rather than piecemeal demolition.

Dismantling each tower bit-by-bit would have involved considerable risk to people working at height and would have reduced the structural integrity making the tower more vulnerable to inadvertent collapse.

On the other hand, assessing the use of explosives on a nuclear licensed site was novel. The principal potential hazards to the reactor buildings were identified as:

- Flying debris

- Ground vibration

- Air overpressure

- Dust blocking of dry air filters

- Inadvertent detonation of explosives during handling

To address the first of these, for example, the explosive charges were placed to remove approximately two thirds of the circumference and the shell legs, causing a controlled collapse away from the reactor buildings, with the resulting rubble designed to fall largely within the footprint of the cooling towers.

There was also initial concern that the ground vibrations caused by tower debris hitting the ground would be similar to a major earthquake and could cause loss of reactor support. However, the safety case showed that ground vibrations would not induce a significant response in the foundations.

Before demolition could take place a number of regulatory submissions were produced by the operator, BNG, with support from Risktec, including:

- A Best Practicable Environmental Option report

- An environmental risk assessment

- The nuclear safety case

AFTERMATH

Witnessed by hundreds of onlookers and broadcast over the internet, the cooling tower demolition proceeded as planned. The only damage sustained was two broken windows in the reactor buildings.

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 12.