Thinking power: avoiding mental traps in risk-based decision making

In his international bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman (winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002) describes mental life by the metaphor of two agents, called System 1 and System 2.

System 2, the slow thinker, is deliberate. It is in charge of selfcontrol. It is much too slow and inefficient at making routine decisions. But it can follow rules, compare several attributes and make deliberate choices between options. It is capable of reasoning and it is cautious.

System 1 on the other hand is the fast thinker, it is impulsive and intuitive. It is more influential than your experience may suggest and is the secret author of many of the choices and judgments you make. It operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort. It executes skilled responses and generates useful intuitions, after adequate training, but is the source of many mental traps or ‘biases’. Despite what you might believe, high intelligence does not make you immune to these psychological biases and there are many biases which can have a profound impact when making risk-based decisions. This article briefly introduces just three of these.

GROUPTHINK BIAS

Groupthink is the desire for harmony or conformity within a group which results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome – very few people like to be the ‘odd one out’. Groupthink was a significant contributor to the Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout in 2010 (Ref.1). The culture of drillers is of a group of highly skilled, opinionated technicians taking a personal interest in every well. They take on a leadership role, in practice if not in definition. The complexity of drilling operations is typically reflected in an obscure language with extensive use of technical slang and acronyms. What is more, peer pressure is extensive, with widespread use of teasing and competitive humour. ‘Dumb’ questions are not well received.

So it is perhaps no surprise that when one of the drillers proposed the ‘bladder theory’ as an explanation for the failed pressure test of the well integrity – a theory with no credibility in hindsight – the first and then eventually the second of the two company men in charge agreed despite initial scepticism. The failed test was ‘reconceptualised’ and the operations continued.

CONFIRMATION BIAS

Confirmation bias is the unconscious tendency of preferring information that confirms your beliefs – a tendency to selective use of information, while giving disproportionately less consideration to alternative possibilities. Put more simply, we see and hear what fits our expectations.

The Lexington aircraft crash in the USA in 2006 is a case study in confirmation bias (Ref. 2). A regional jet took off from the wrong runway in darkness and failed to get airborne in sufficient time to clear trees at the end of the runway, causing the deaths of 49 passengers and crew. Multiple cues were missed by the pilots that should have alerted them to the fact that they were on the wrong runway. Instead, it is believed that the crew talked themselves into believing they were in the correct position. For example, in response to a comment about the lack of runway lights, the first officer said that he remembered several runway lights being unserviceable last time he had operated from the airfield.

AVAILABILITY BIAS

Availability bias means you judge the probability of an event by the ease with which occurrences can be brought to mind. You thus implicitly assume that readily-available examples represent unbiased estimates of statistical probabilities.

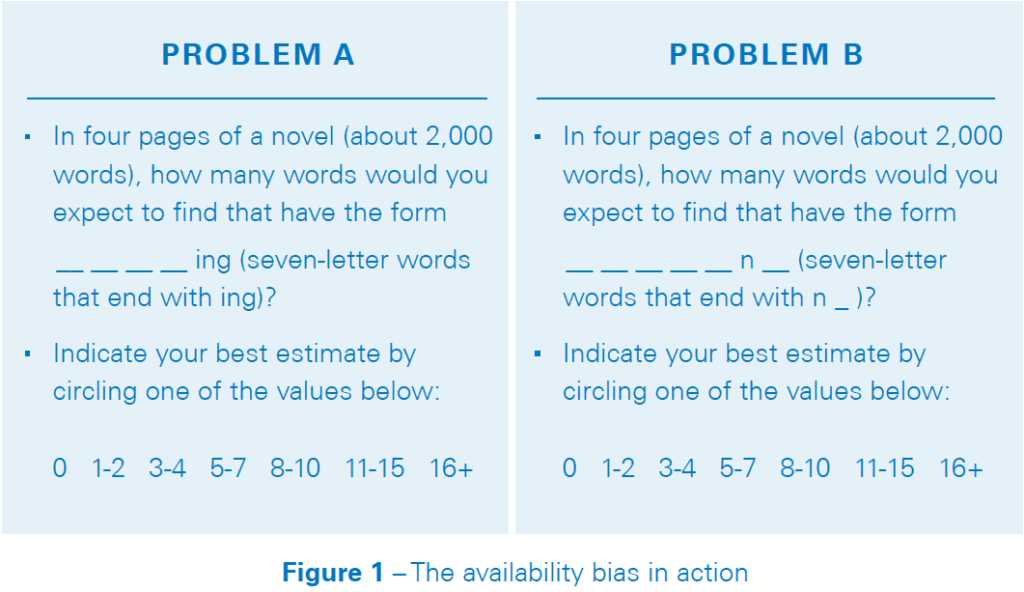

Try the simple test in Figure 1 before reading on.

If you answered a higher number for Problem A then you are in good company – most people do. But all words with seven letters that end in ing also have n as their sixth letter. Your fast thinking System 1 has fooled you. Ing words are more retrievable from memory because of the commonality of the ing suffix.

The availability bias can create sizeable errors in estimates about the probability of events and in relationships such as causation and correlation. Be aware, your risk analysis assumptions may not always be right, especially when they are backed by quick judgements

SO WHAT’S THE REMEDY?

Think slow! Engage your System 2. Control your emotions and the desire to jump to conclusions. Take your time to make considered decisions and be ready to ask for more evidence, especially when pushed to make a fast decision. Request explicit risk trade-off studies. Challenge groupthink, and base your opinion on facts. Never be afraid of speaking up, you could save the day.

Consult widely and generate options.

Involve a diverse group of people and don’t be afraid to listen to dissenting views. Seek out people and information that challenge your opinions, or assign someone on your team to play ‘devil’s advocate’. Learn to recognise situations in which mistakes are likely. Try harder to avoid mental traps when the stakes are high. And finally, practice, refine, practice.

CONCLUSION

It is human nature to think in short-cuts, which bring with them a host of associated psychological biases. When making risk-based decisions it is essential to slow down our thinking, and apply formalised processes backed by science and data.

References:

- Disastrous Decisions: The Human and Organisational Causes of the Gulf of Mexico Blowout, Andrew Hopkins, 2012.

- Accident Report, NTSB, AAR-07/05, 2007.

This article first appeared in RISKworld issue 31