Remote Control – The art of delivering successful workshops remotely

Conventional wisdom has it that structured workshops of a technical nature are best delivered face-to-face in a meeting room with all the technical props and people in one place, interacting dynamically to achieve a common goal. With the coronavirus-related restrictions imposed on travel and social contact, this approach is no longer possible in most countries. Can remote working really offer a viable alternative? And if so, how?

NEEDS MUST

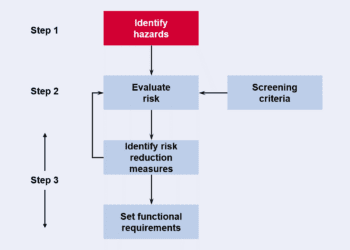

Structured technical workshops, such as might be used for Hazard and Operability (HAZOP), Hazard Identification (HAZID) and Layers Of Protection Analysis (LOPA) studies, have traditionally been delivered face-to-face, with the workshop team sat around a large table, led by a facilitator and recorded by a scribe. Running such workshops remotely was uncommon, and usually only contemplated when the duration was short, perhaps a day or two, and the logistics of bringing together the workshop team were prohibitive, for example, in locations with civil unrest or military conflict.

However, constraints on travel and working practices arising from the global outbreak of coronavirus have necessitated that such workshops cease or run remotely. Whilst the benefits of pressing on are obvious, the concern is that the quality of the output will not be as high as face-to-face meetings and important issues may be missed. To address these concerns, it is worth reflecting for a moment on the factors that make face-to- face workshops successful.

SOCIAL ANIMALS

Face-to-face workshops have been the norm for very good reason – they can be energising, collaborative and productive when facilitated properly. They allow people to interact, discuss issues thoroughly and build synergy.

Physical meetings tap into our innate desire to socialise and our interactions highlight the difference between simply holding a conversation and building a productive working relationship. We all communicate through non-verbal cues: body language, physical contact (a handshake or a hand on a shoulder), laughter, and facial expressions all build rapport and provide context. Without these, communication can feel awkward and may be incomplete. When we meet people face-to-face, we’re likely to chat and make small talk, share tea and coffee, lunch – all of which can help build a connection. In a workshop setting, non-verbal cues can be interpreted by the facilitator to assess reactions to concepts and opinions, and ensure the best is brought out of all participants. Similarly, participants will contribute positively and proactively if they feel part of the group and are encouraged by both the facilitator and the nonverbal cues of others.

Around a table, sharing technical information, such as large drawings, 3D models or a live record of findings via projector, is straightforward and inclusive.

REMOTELY GOOD ENOUGH

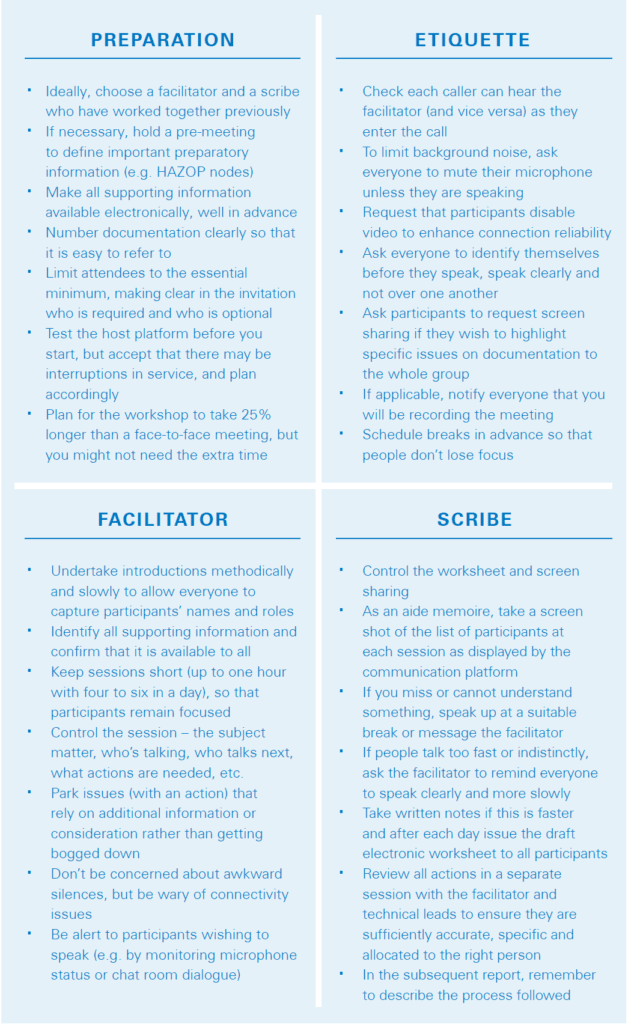

Whilst remote workshops enabled by digital communication cannot quite live up to these outcomes, particularly in terms of rapport, technically they can be as efficient and effective if properly prepared and expertly facilitated – see Table 1 for tips and hints. The essential keys to success are to:

- Make all supporting information available electronically.

- Test the host platform before you start, but accept that there may be interruptions in service, and plan accordingly.

- Keep sessions short, so that participants remain focused.

- Adopt a clear participation protocol and make sure this is highlighted at the start of every session.

Table 1 – Top tips for remote workshops

If these and other tips are followed, there is an argument that remote workshop can be more focused and more productive than corresponding face-to-face meetings. Economically, they are, of course, cheaper because no travel and accommodation costs are incurred. But the key question is whether critical safety issues are more likely to be missed in a remote environment compared to face-to-face? If the participants are the same, the underlying method is the same, the preparation the same (or possibly more extensive) and the facilitation and recording are equally comprehensive, then there is no obvious reason why remote workshops should be more vulnerable to oversights.

CONCLUSION

In the face of unprecedented restrictions on normal working life brought about by the coronavirus pandemic, remote workshops are being adopted as a practical way to make progress. Whilst replicating the richness of social and visual interactions associated with face-to-face meetings is too much to hope for, an expertly planned and executed remote workshop can still deliver a quality, technical outcome.