A hazard missed is a hazard uncontrolled

“The identification of areas of vulnerability and of specific hazards is of fundamental importance in loss prevention. Once these have been identified, the battle is more than half won.” (Frank Lees)

It would seem reasonably self-evident that we can only manage risks that we are aware of. However, far too many accident investigations and inquiries, for example the Longford gas explosion and the Nimrod XV230 crash, point to inadequate or inappropriate hazard identification as being a root cause.

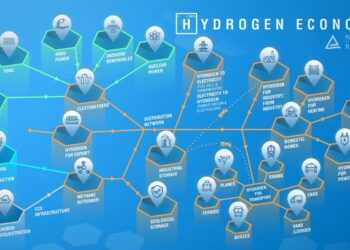

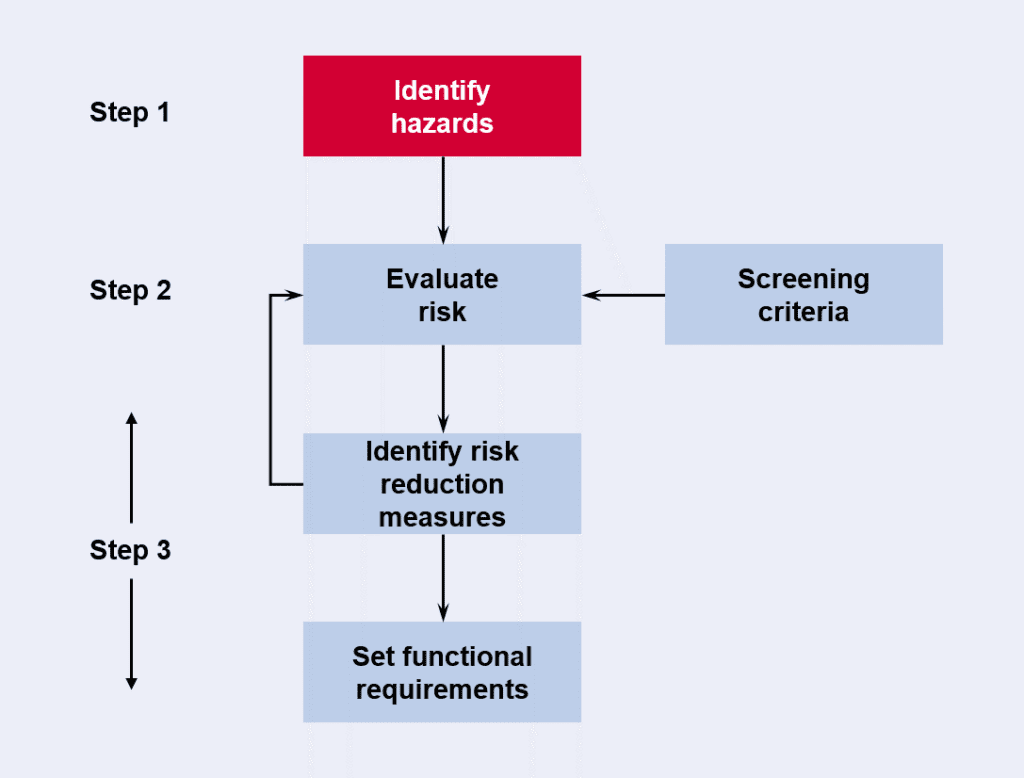

International standards and guidance [e.g. Refs 1, 2, 3] clearly show the importance of this key step [see figure 1], but leave open the question “How do we actually identify the hazards?”. There have been attempts to try to develop advanced, automated and all-encompassing methods, but none have gained mainstream acceptance because either they are simply too complex to apply in practice, or end-users fear the ‘black-box’ output will be accepted without challenge. As a result, in general, there are four standard techniques that are most commonly used.

Hazard and Operability Study (HAZOP)

A HAZOP study consists of applying a set of guidewords (e.g. pressure, flow, temperature, etc.) to defined aspects of a design and challenging these with deviations (e.g. no, more, less, etc.). It is principally applied in a workshop environment to review process design but can also be applied, with altered guidewords, to railway systems, oil well design, procedural activities, etc.

Failure Modes & Effects Analysis (FMEA)

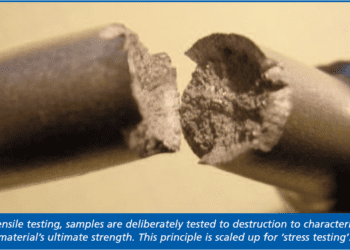

FMEA is a systematic review of the failure modes of an equipment item, e.g. pump, or system, e.g. Blowout Preventer, and their effects. It may also be extended to classify the severity (or criticality) of failures (FMECA). Although generally undertaken as a desktop exercise, workshops may also be held.

Checklists (HAZID)

Checklist applications range from identifying workplace hazards through to major events. Primarily a ‘brain-storming’ approach performed in a workshop environment, it is very dependent on appropriate checklist selection and the experience of the team.

What-If

What-If is also a team-based review using checklists, but may be more freeform, involving experienced personnel questioning possible deviations, e.g. “What if the wrong material is delivered?”

Figure 1 – Identifying hazards is the first step of the risk assessment process (Ref. 2)

THE KEY TO SUCCESS

The key to successful hazard identification involves:

Choosing the right tool for the job

There is little point in trying to force through a technique if it is not comprehensible to the personnel involved, or if there is insufficient information available for it to be meaningful. Similarly, performing a review requiring detailed drawings at a project stage where only sketches are available will prove frustrating.

Involving the right people

The majority of hazard identification techniques rely on some form of group consensus reached in a workshop and are a product of the experience, knowledge and agendas of those involved. Failure to have suitably experienced personnel in the room can result in hazards being missed or incorrect information being recorded, though having an experienced but insular group of personnel can also mean that existing arrangements remain unchallenged.

Having the right mindset

Although we must be mindful of historical events as a guide to what can happen, it is also important to keep an open mind and ‘think outside the box’ in terms of what might happen. Simply because a specific accident hasn’t happened before does not mean that it can’t happen.

SUMMARY

Hazard identification is the first step of the risk assessment process and a hazard missed is a hazard uncontrolled. There are many tools and techniques available, but no ‘one size fits all’. The key to successful identification lies in choosing the right tool for the job, involving the right people and being prepared to challenge the status quo. It is also worth remembering that hazard identification is a continual process; designs evolve, conditions change, processes move on – all operations require periodic revalidation of the hazards present.

References

1. Five Steps to Risk Assessment, UK Health and Safety Executive

2. Tools & Techniques for Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment, ISO 17776:2000

3. Risk Management, ISO 31000:2009

FURTHER READING

1. Hazard Identification Methods, European Process Safety Centre

2. Review of Hazard Identification Techniques HSL/2005/58, UK Health and Safety Laboratory

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 18