No Need for Alarm? The Art of Alarm Management

The design philosophy of any alarm system is to alert the operator to a plant condition that has reached or exceeded a pre-defined limit, so that he or she can take action or monitor any automatic response.

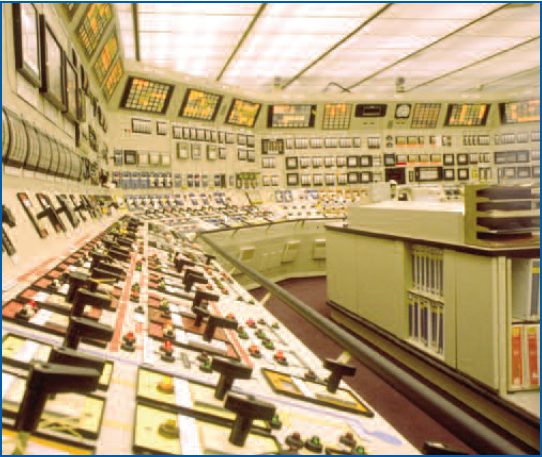

TOO MUCH INFORMATION

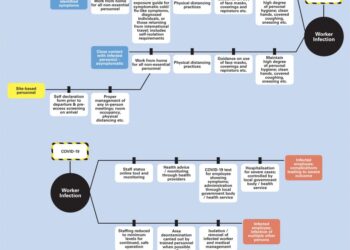

Historically, as organisations have begun to make formal claims upon alarms within safety cases as a line of protection against a specific fault condition, they have gained a much higher prominence. At the same time, the growing capability of modern alarm systems (both hardware and software) has made the provision of alarms relatively simple, leading to a proliferation in the number and diversity of alarms. Coupled with increasing plant complexity, the control room operator is often faced with a huge array of alarms, covering many scenarios. This can make it challenging to differentiate between the alarms that are important and those that are not, and to diagnose the root cause of the problem.

To compound the issue, as the plant ages and is modified, alarms can be rendered redundant or may be replaced with alternative indication.

Incorrectly configured alarms can cause frequent spurious alarms which can introduce a culture of complacency where a real alarm could fail to prompt a timely operator response.

MODERN ALARM MANAGEMENT

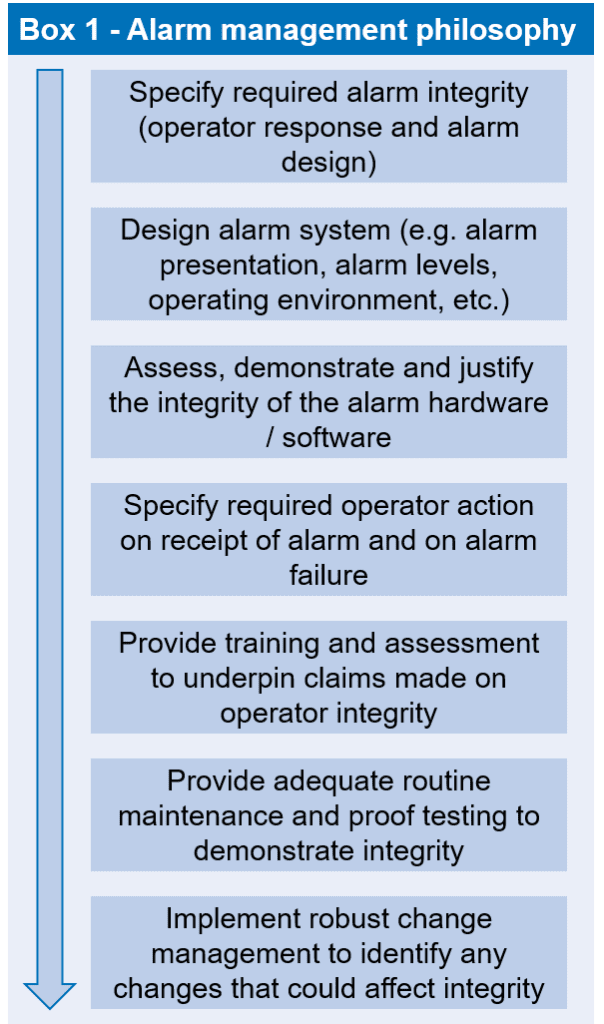

A modern plant requires a robust alarm management philosophy. This identifies the purpose, importance and priority of each alarm, action to be taken on alarm failure, operator training and a robust management of change process (see Box 1).

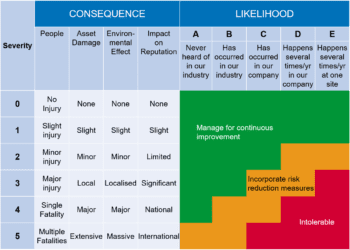

Where operator response is claimed in a safety case, the alarm should be unambiguous and directly traceable to the hazard. Techniques such as Bowtie analysis can provide a visible link between the hazard and the alarm condition and clearly highlight the requirement for operator training, procedures and maintenance arrangements. This helps ensure that the safety integrity claimed for the alarm can be achieved, and supports any justification required of the Human Error Probability associated with operator response (e.g. for use in PSA/QRA – see Page 6).

The presentation of the alarms should be carefully considered and reflect the operating conditions. In this regard, human factors assessment is an integral and important part of system design and aims to ensure that alarms cannot be missed, masked or mistaken.

The number of configured alarms should be rationalised and minimised, with each alarm configured to minimise spurious activation and provide clear information to the operator, supported by procedures and training.

Ongoing performance monitoring is essential to ensure that frequent alarms are identified and the root cause investigated. Changes to the plant may require re-assessment of alarm systems.

CONCLUSION

Failure to manage alarms properly undermines the operator, the safety case and plant safety. By having a robust alarm management system in place, the operator has the best chance of taking the correct action when required.

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 22