Fatigue risk management with bowties

Fatigue is a major issue for organisations with shift working patterns, especially those with long or irregular hours. Where facilities operate 24/7, extended wakefulness, inadequate sleep and night work can be common and it is impossible to totally eliminate fatigue from the workplace.

Traditionally, organisations have adopted a prescriptive approach to managing fatigue that focuses primarily on controlling the hours an individual can work per shift, minimum break times, maximum number of sequential shifts or the cumulative number of hours worked in a given period.

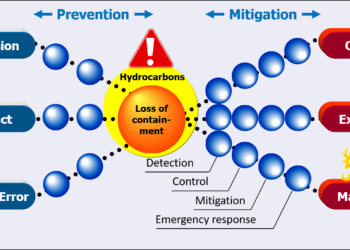

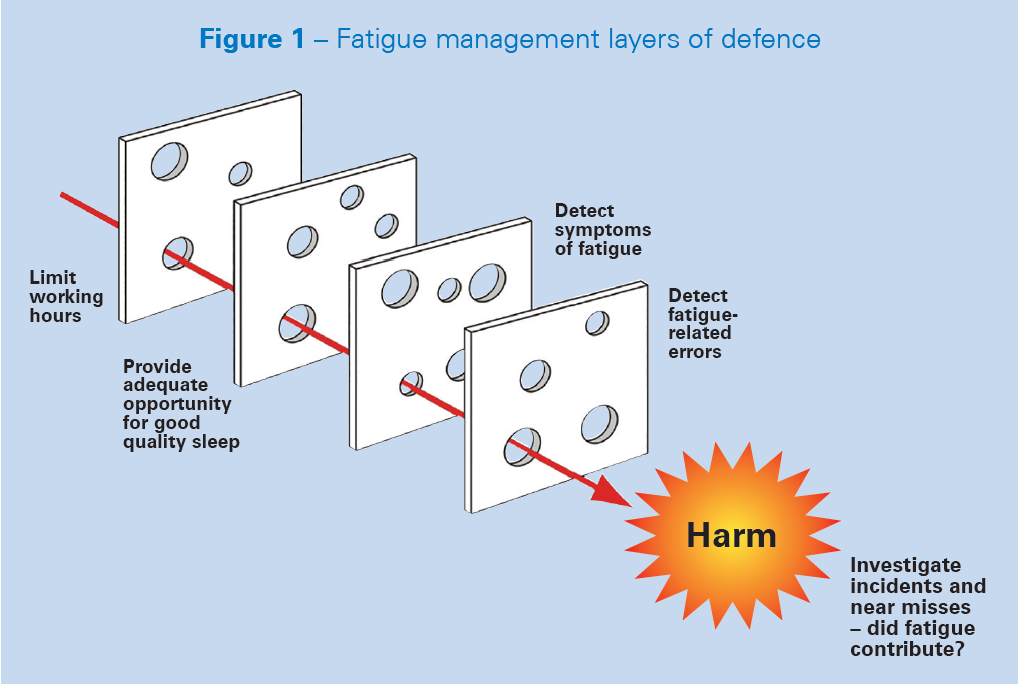

Whilst compliance with limits on working hours has a valid role to play, in recent times fatigue management has moved towards a more flexible and multi-layered approach (see Refs. 1 and 2), where prescribed working hours are only the first layer in several lines of defence (Figure 1).

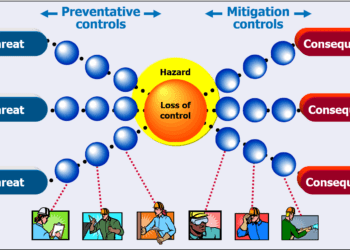

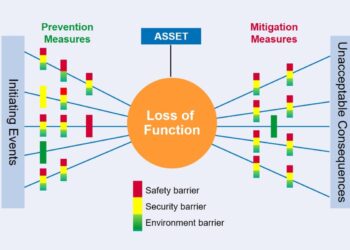

Of course, fatigue can be managed in the same way as any other workplace hazard. Risk assessment techniques can be adapted to identify the causes and consequences of fatigue and ensure that a variety of prevention and mitigation measures are implemented to provide the multiple layers of defence described in Figure 1. The identified measures can then be implemented through a structured fatigue management framework, which becomes an integral part of the organisation’s overall health and safety management system.

BOWTIE ANALYSIS

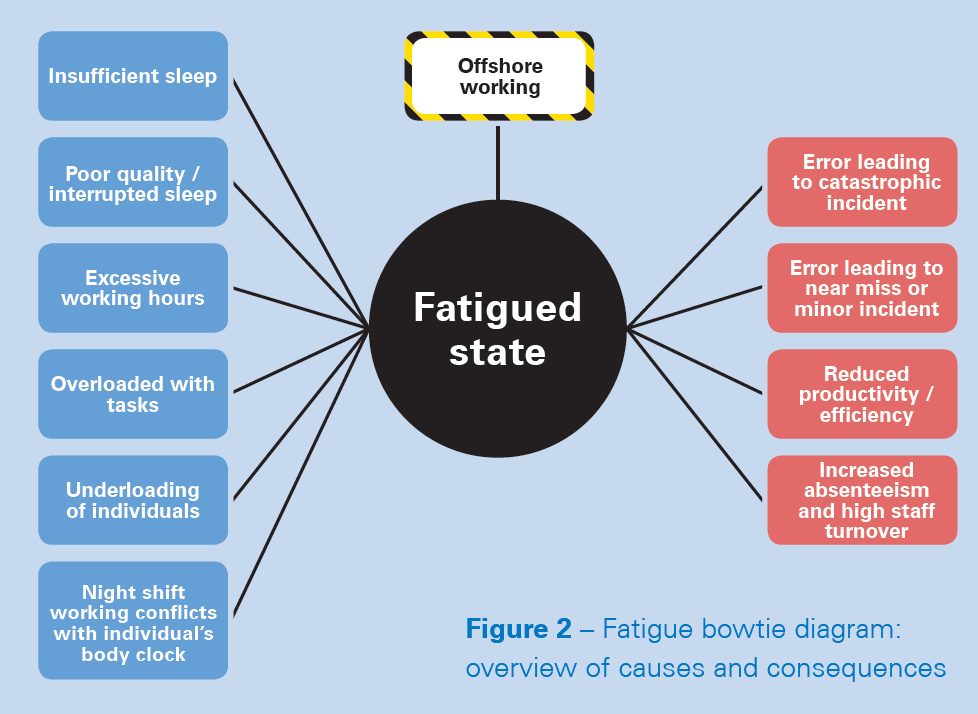

One proven approach to developing a risk-based fatigue management framework is to apply bowtie analysis. This ensures that the framework targets the location- and activity-specific causes and consequences of fatigue for specific operators. Given the bowtie diagram structure, with its origin in the Reason ‘Swiss cheese’ model, bowtie analysis is an ideal way of identifying, evaluating and demonstrating multiple layers of defence for managing fatigue.

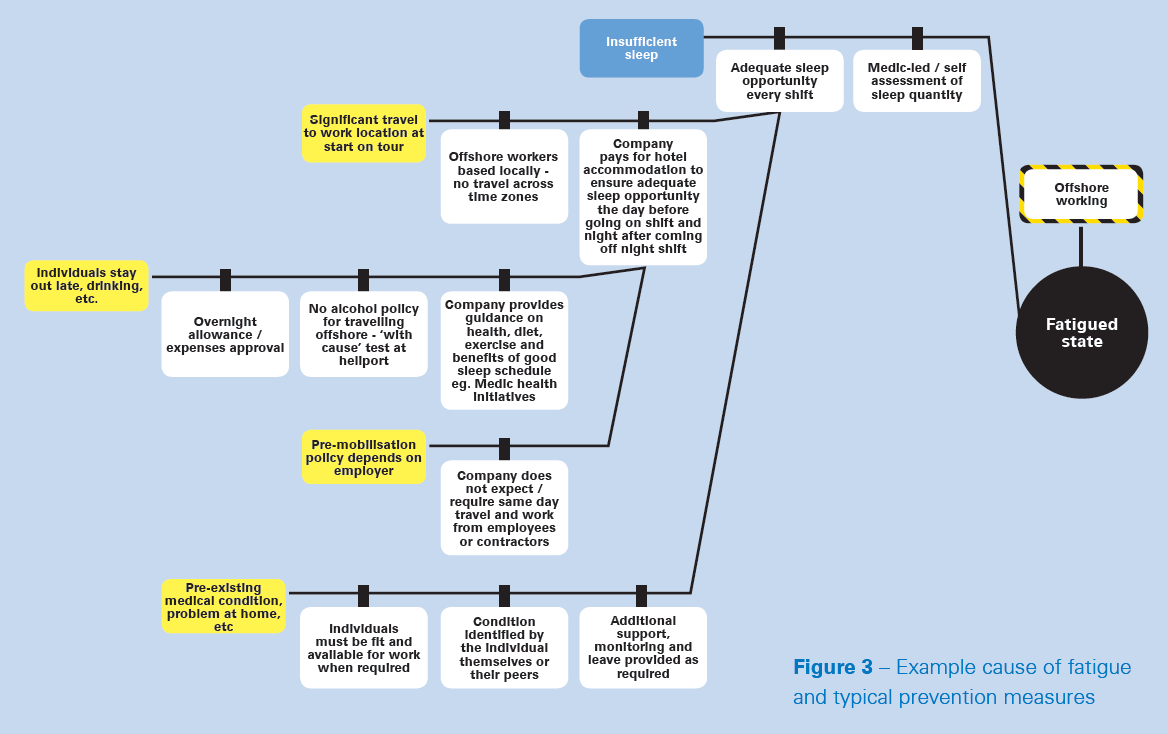

A bowtie diagram is straightforward to develop from relevant good practice (e.g. Refs 1 to 5) and a multi-disciplinary workshop involving managers, supervisors, operators and safety representatives. The team identifies ways in which the organisation could adopt specific tools to address gaps between current arrangements and fatigue management good practice. The workshop also considers further risk reduction measures, in order to reduce fatigue risk to ALARP levels. All resulting bowtie prevention and mitigation measures (i.e. those currently in place at the time of the assessment, plus additional measures agreed for implementation) can be captured in the framework.

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Extracts from an example bowtie diagram are shown in Figures 2 and 3. The diagrams illustrate that responsibility for managing fatigue in the workplace is shared between an organisation and its employees. Certain prevention and mitigation measures are within the control of the company, others are controlled by the individual. Similarly, although company-wide measures are sufficient to manage the majority of the risk, case-specific additional controls may be required to ensure sufficient layers of defence. For instance, these may include:

- Review of sleep quality and quantity and the identification of improvement measures.

- The dynamic assessment of fatigue symptoms by the individual, his peers or supervisor.

- Flexible strategies for reacting to fatigue, such as exercise, short breaks or task rotation.

The bowtie provides an easy-to-use template for an organisation to assess its fatigue management arrangements for each operating asset against the requirements of its fatigue management framework and good practice, e.g. by auditing against the barriers shown on the diagram. Should fatigue be indicated as a contributing factor to an incident, the bowtie also provides a starting point for determining failure mechanisms and underlying root causes.

CONCLUSION

Clear communication of hazards and their controls is a recognised benefit of bowtie analysis. In this case, the bowtie diagram illustrates, in a readily-understandable form, what an organisation is doing to safeguard its workers against fatigue and what the workers can do for themselves.

References:

1. Energy Institute, Managing Fatigue Using a Fatigue Risk Management Plan (FRMP), 2014.

2. CRC Australia, Developing a Framework for a National Standard in fatigue risk management in the Rail Industry, R2.109, 2014.

3. Health and Safety Executive, Managing Shiftwork, Health and Safety Guidance, HSG256, 2006.

4. Health and Safety Executive, Guidance for Managing Shiftwork and Fatigue Offshore, Offshore Information Sheet 7-2008.

5. IPIECA, OGP, Managing Fatigue in the Workplace, OGP 392.

This article first appeared in RISKworld issue 32