Quantitative assessment of multi-facility risks

Operators of major hazard facilities are required to understand and manage the risks presented to their workforce, the general public and the environment. Complications can arise when multiple facilities are located in close proximity, as each will contribute to the risks at neighbouring facilities.

In some cases, such as large industrial cities in the Middle East, a large number of hydrocarbon processing facilities are co-located in the same super-complex. Citywide risks are important in such situations for land-use planning, determining sites suitable for further process facilities or for worker camps.

For offshore developments of extensive oil and gas fields, there may be multiple platform hubs with drilling centres and processing trains, each with significant hazard ranges. Field-wide risks are important when assessing separation distances and scheduling construction teams, particularly in fields where the highly toxic hydrogen sulphide is present.

So how can we assess city or field-wide risks for a multi-facility development?

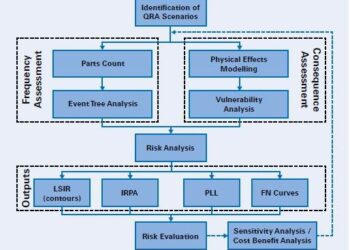

SINGLE QRA MODEL SOLUTION

The natural solution is to develop a conventional quantitative risk assessment (QRA) model to cover the whole complex or field. This approach can present many technical challenges. Although each facility will usually already have its own QRA, these may have been developed with different rule sets and assumptions, so a process of rule set alignment with relevant stakeholders would be required initially. The QRAs may also have been developed in different custom or commercial software packages, further complicating the integration process.

The size of the final QRA model also needs to be considered, as a direct combination of individual facility QRAs could lead to a large and cumbersome model, taking significant computational power to process – or even exceed the limitations of the software. A screening process to remove events with no potential for off-site impact would be required to mitigate this, on the understanding that ensuing results should only be used to analyse off-site impact. Nonetheless, it follows that developing an over-arching QRA model can involve substantial effort.

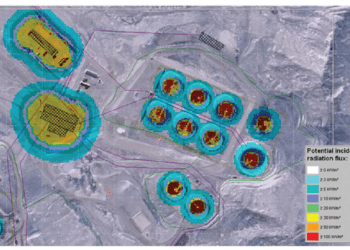

ALTERNATIVE SOLUTION

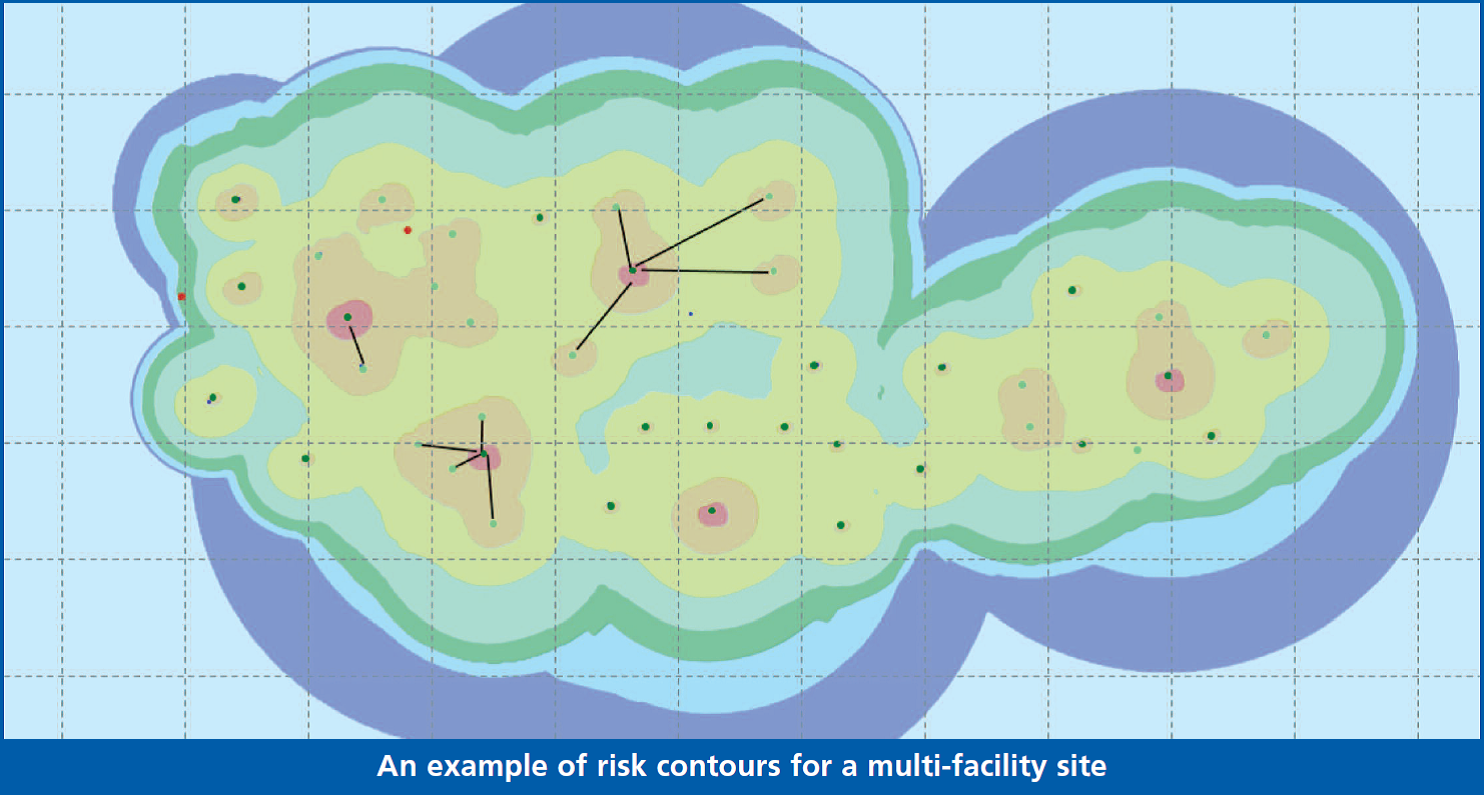

An alternate approach to consider before committing to an integrated model is to explore ways of exploiting the results of the existing QRAs. Bringing these together in a faster (albeit coarser) fashion has several advantages and can give useful results in a fraction of the time. One example is the use of the data behind the contour plots traditionally generated in onshore QRAs. Most QRA packages are able to export the underlying risk data generated from the model on a regular grid of points across a geographical area. These individual risk outputs can be combined on a common site-wide grid using simple translation and interpolation operations to produce risk contours spanning the full site.

As there are no risk calculations being performed, there is no dependence on specialist QRA packages and processing is fast. The relative locations of facilities can be quickly updated, with changes to the risk profile visualised almost instantly without long simulation times, giving a real benefit in situations where a multitude of potential layouts are being assessed. In this case, although the detailed contribution from specific events is lost, the overall benefits are realised for a fraction of the cost of an integrated QRA.

CONCLUSION

Developing QRAs spanning multiple major hazard facilities can be a challenging and time-consuming process. Coarser results-based strategies have the potential to short-cut this, allowing city or field-wide risk profiles to be generated in a much shorter timescale.

This article first appeared in RISKworld issue 25