Balancing personal and system safety

Holding the handrail and putting lids on cups of hot coffee will not prevent major accidents. That is the message coming through loud and clear in the aftermath of recent disasters such as the Texas City refinery explosion in 2005, the Gulf of Mexico oil well blowout in 2010 and the Fukushima nuclear meltdown in 2011. Disasters don’t happen because someone slips down the stairs or bumps their head. They result from flawed ways of doing business that allow inappropriate risk control.

Many organisations implement initiatives and campaigns aimed at promoting personal safety in the workplace, both in attempts to achieve a measurable step change in safety performance and to demonstrate corporate commitment to good safety culture. This is very important, but don’t expect those actions to lead directly to improved system safety, which concerns the integrity of the process or operations. Indeed, the year before the Texas City explosion the refinery had its lowest injury rate in history, nearly one-third of the oil refinery sector average.

DIFFERENT APPROACHES

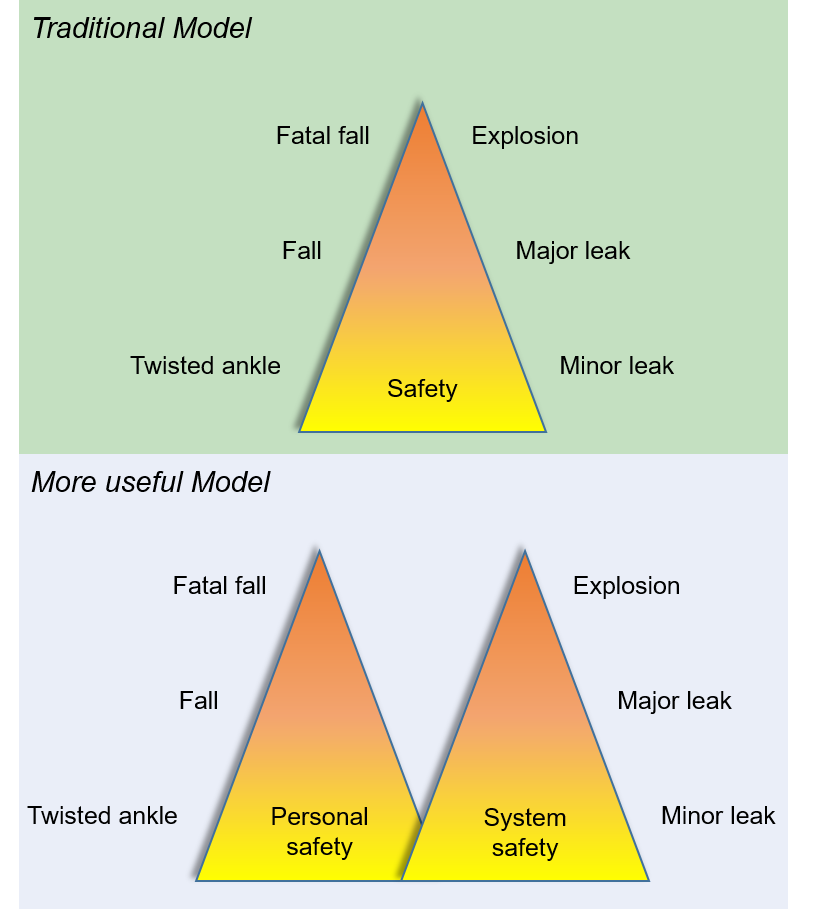

The traditional ‘accident pyramid’ model mixes together personal safety and system safety. This is not very helpful because it implies “holding the handrail” will prevent an explosion. Today it is a far more useful concept to view the situation as two separate pyramids with some overlap.

Figure 1 – Contrasting hazard models

The role of incorrect mental models that don’t reflect what actually happens is well documented in major incidents, e.g. Three Mile Island, where operators believed a coolant leak could not lead to a rising coolant level (although this was well understood scientifically). So if management’s mental model is that personal safety initiatives will prevent major accidents, is there a blindness to major risk? Moreover, what message is really being sent to staff by rolling out an occupational safety initiative at a facility with a history of leaking pipes?

Furthermore, what works for one company or location in achieving safe operations may not be applicable to another. For example, the portfolio of risks present for a major hazard site such as a refinery will be very different to a manpower intensive, low hazard environment like an office, as will the way in which those risks are managed. It would be reasonable to suggest that the former will require both occupational and system safety approaches, whereas the latter will be primarily focused on occupational issues.

DIFFERENT MINDSETS

With occupational safety there is a direct and visible link between the action (holding the handrail) and the benefit (avoiding a fall). As such it is generally easier to make improvements by bringing about changes in safe behaviours, and its traditional lagging metrics, e.g. loss time injuries, are familiar and easy to measure.

Creating the right mindset is not an effective strategy for dealing with hazards about which workers have no knowledge…

System safety on the other hand is less visible and more complex because it focuses on the integrity of the design, operation and maintenance to prevent major incidents. Its metrics, particularly proactive ones (e.g. percentage of safetycritical equipment that performs within specification when inspected) are harder to define, measure and interpret. Although there is some overlap, believing that improvements in one means that the other is also improving is at best misleading, and at worst, dangerous.

Having a mindset to hold a handrail is not in itself a bad thing – it’s simple, costs nothing and may prevent a fall, but is it really rational to assume that this will prevent a pipeline leak? Yes, the mindset may mean that personnel are more proactive in major accident safety, but what really matters is top down leadership – that leaders have a focus on system safety when allocating resources and making decisions, that any cost-cutting is managed effectively, that bonuses are not solely tied to personal-injury metrics – and that the plant is properly designed, operated and maintained by competent personnel.

UNDERSTANDING RISK

While, globally, occupational hazards kill and injure more people than major accidents events, a single catastrophic event can wreak widespread harm and jeopardise the survival of an entire organisation. So where should an organisation focus its efforts? This comes back to the very crux of the issue – an organisation that does not clearly understand its full spectrum of risks will not be able to manage those that are important.

CONCLUSION

The benefits of personal safety based initiatives are clear; properly conceived and implemented they will minimise injuries and save lives. But they should be viewed as one part of a balanced approach to risk management, based on a clear understanding of the wide landscape of risks faced by an organisation, and its leadership practices, culture and approach for assuring safety across the whole business.

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 22