A rough guide to hydrogen sulphide

Around one-third of the world’s gas fields contain ‘sour gas’, contaminated by sulphur compounds including hydrogen sulphide, also known as H2S. This gas is one of the most deadly hazards in the industry, making the fields more difficult to develop.

As the fields with low levels of contaminants become depleted, the industry has looked to exploit formations of sour gas to meet the demand of the world’s growing energy needs. The end result is ‘sweet gas’, profitably extracted and processed in accordance with increasingly stringent health, safety and environmental requirements.

Safe production from sour gas fields is not new – there are numerous existing facilities such as those in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains of Alberta, Canada, that have many years of safe operation. However, some of the world’s largest new projects are developing sour gas reservoirs, such as those in the north east corner of the Caspian Sea and in the deserts of Oman, and they are applying increasingly effective design strategies and technologies to manage the risks.

H2S HAZARDS

You can detect the presence of H2S at less than 1 part per million (ppm) – it is easily recognised by its characteristic foul odour similar to rotten eggs. Unfortunately, it may be the last thing you ever smell. If the concentration of the gas is above 100 ppm the sense of smell is quickly deadened, giving a false sense of security that the danger has passed. Concentrations above 500 ppm can lead to breathing difficulties and confusion, and above 700 ppm immediate unconsciousness. 1000 ppm will lead to death unless rescued promptly [see Box 1].

Box 1

H2S creates another problem – it causes iron to corrode and equipment such as valves and flow lines to malfunction and leak [see Fig 1]. So not only are the effects of an inadvertent release of H2S far more harmful than conventional gas, H2S itself makes a leak more likely.

Figure 1 – Signs of hydrogen sulphide corrosion include shallow round pits with etched bottoms

CONTROLLING THE H2S RISK

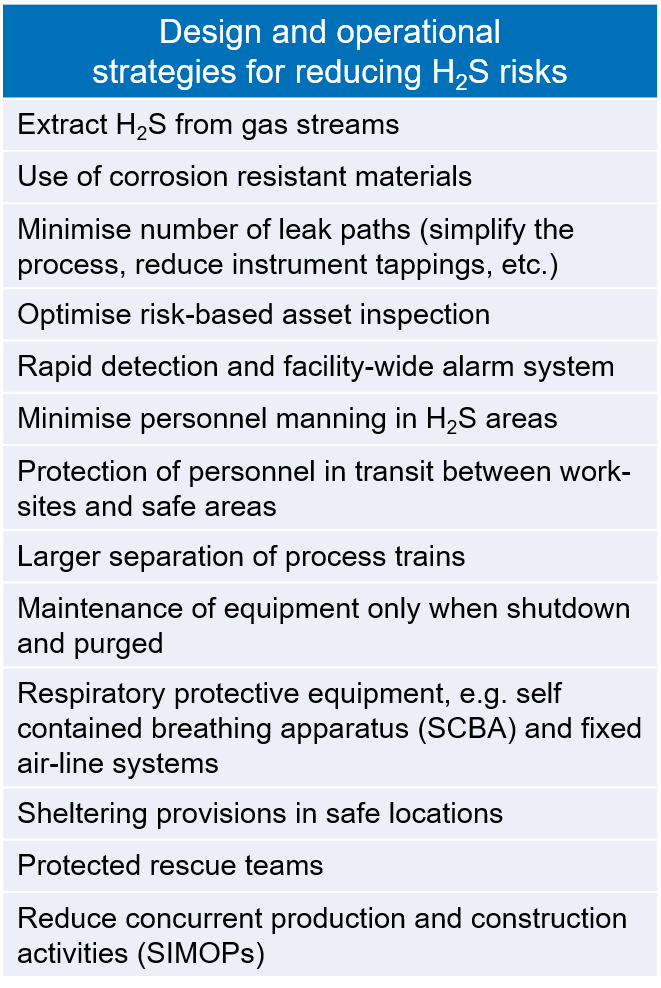

Managing H2S safely requires design barriers that serve to prevent releases and alert workers should a leak occur, and operational barriers that limit their potential exposure. A selection of design and operational strategies for reducing the risks associated with H2S are shown in Box 2.

Box 2

TO ENCLOSE OR NOT TO ENCLOSE?

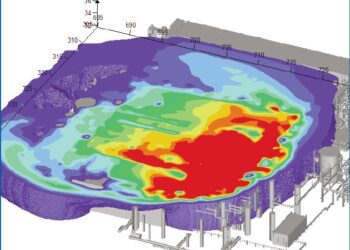

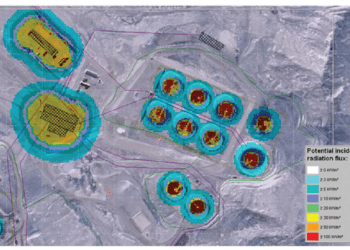

It is common practice in the oil and gas industry for hydrocarbon processing facilities to be situated in the open, exposed to the natural elements. There are some significant safety benefits to this strategy. For example, any gas release may be naturally diluted to below toxic levels or to below the level where it could result in an explosion.

However, many new projects for sour gas fields are also in an extremely cold or hot climate, or both. Some of these projects are considering enclosing the process plant to realise significant operational and maintenance benefits, e.g. easier and faster working for personnel, and less wear and tear of the equipment from the weather. Such enclosures could be heavily engineered modules like those on some offshore platforms.

From a safety perspective, the issue is not clear cut. At first glance it would appear that workers inside an enclosure would be more readily exposed to H2S should a leak occur, i.e. the gas can’t dilute in the open air to below fatal levels. But there are ways of overcoming this, for instance a high specification ventilation system and vent stacks to safely extract and disperse the gas, a requirement for workers to only enter the enclosure when wearing breathing apparatus [see Fig 2], or only allowing maintenance of equipment when plant is shutdown and the gas removed.

Furthermore, a major safety benefit of enclosing the plant is that, with good vent stack design, workers outside of the enclosure would not be exposed at all to any releases inside the enclosures, unlike open plant where all workers downwind of a release could be affected.

There are other safety issues to consider, such as fire and explosion protection, but the industry is tackling every issue head-on to ensure that all risks are reduced and controlled to acceptable levels.

CONCLUSIONS

The search for new oil and gas is increasingly requiring the development of sour gas fields. Effective risk management strategies are required to prevent leaks of H2S and protect workers and the public from its lethal effects. The industry faces many technical challenges, but is rising to meet them with innovative design solutions and new technologies.

References

1. United Nations Environment Programme: [https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency]

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 15.