Applying QRA more widely

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in extending the scope of quantitative risk assessment (QRA) beyond the risk to people to look at areas such as environmental damage, economic impact and the effect on reputation. High profile accidents with widespread consequences, such as Deepwater Horizon, Buncefield and Fukushima, have left many organisations with a desire to understand better their exposure across the whole spectrum of potential risks. But how easy in practice is it to apply QRA more widely?

TRADITIONAL SAFETY QRA

QRA in the oil and gas industry, for example, focuses on the risk to workers and the general public from major hazards such as fires, explosions and toxic gas release. This process involves identifying the hazards, evaluating the frequency of the various hazardous events and undertaking consequence analysis to estimate the magnitude and effects of the resultant fire, explosion or gas cloud. Geographical information is captured, including the location of the hazardous events and the number and distribution of people. This information and supporting analysis of the hazard progression (taking into account detection, isolation and ignition, for instance) are combined with the vulnerability of people to each hazard to calculate the risk to people.

WIDER EFFECTS

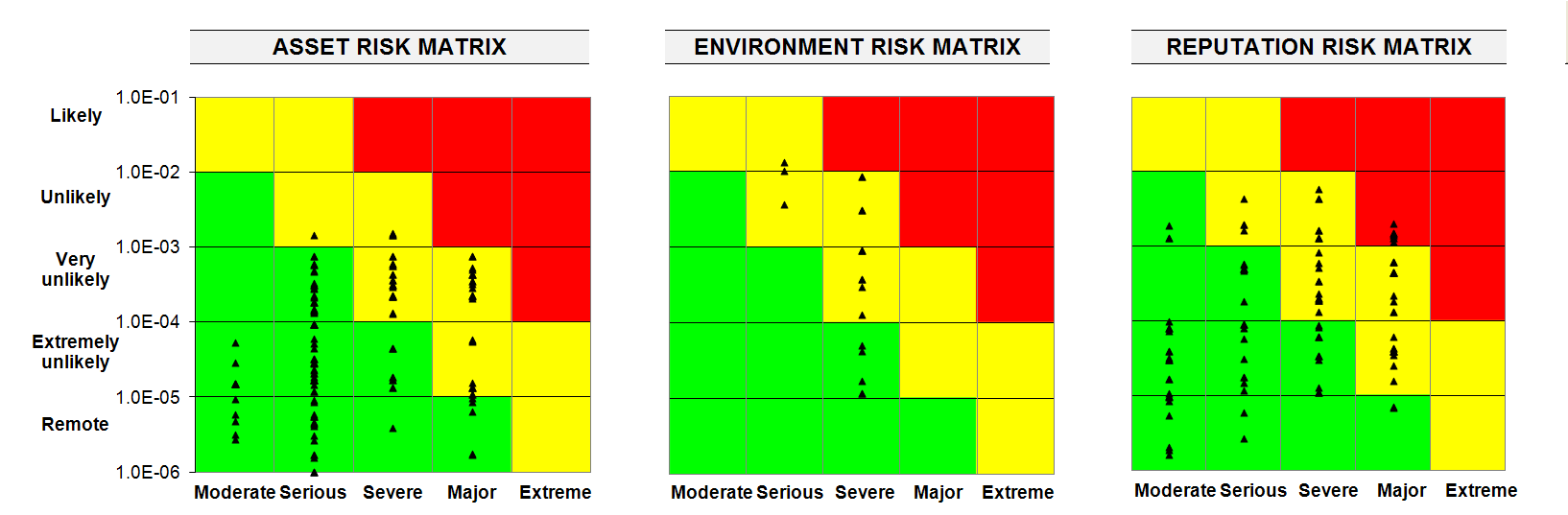

However, hazards may also have other negative effects beyond harming people. Liquid spills may cause harm to the environment, whereas fires and explosions can damage assets and infrastructure. These may lead to lost revenue, regulatory penalties, compensation to third parties, as well as damaging the reputation of the company involved. The information in QRA models can be extended to quantify some of these additional risks. Harm to the environment is normally associated with releases of hydrocarbon or other chemicals either into the sea or onshore where it flows into water courses or permeates into the ground. The volume of release can often be estimated from the process data used in the conventional consequence modelling (release rate, duration and the volume of the isolated inventory). In practice, all potential sources of release would be screened first to determine whether they would reach the environment. While quantifying clean-up costs is feasible, measuring the harm to the environment is more subjective and is perhaps best achieved using a number of discretely defined, qualitative categories (for example see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Semi-probabilistic presentation of QRA results

Damage to assets and infrastructure depends on a combination of magnitude (overpressure or radiation) and in the case of fires, the duration, which may be limited by isolation and depressurisation. For onshore and offshore facilities it is usually straightforward to estimate the repair or rebuild cost. Lost production or processing revenues are sometimes a simple function of the outage period, though in many cases production is actually deferred rather than lost. However, oil and gas blowouts need to factor in the cost of bringing the well under control, which can be very high especially if a relief well needs to be drilled. Regulatory penalties extending to loss of operating licence, compensation to neighbours and the public, and reputation issues are difficult to quantify, but it is usually possible to assign a qualitative indication of the harm, which can be presented as a risk matrix (similar to Figure 1).

CONCLUSION

The analysis of event frequency, event progression and consequences developed in traditional safety QRAs provides a sound platform from which to develop a wider picture of risk that can naturally include environmental, asset and economic factors. This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 23