Pressure system integrity management in the conventional power sector

Failures from high energy steam and hot water pressure parts can result in significant process safety risks and are often associated with costly damage to other assets in the vicinity, loss of plant availability and negative publicity. Serious incidents may also result in prosecution. With numerous factors to consider, such as plant age, history of defects, operating regime, system design, materials of construction, build quality and experience from the wider industry, the development of robust condition monitoring strategies to manage plant integrity and to ensure regulatory compliance is suited to a risk-based approach.

REGULATORY COMPLIANCE AND RISK

Taking the UK as an example, steam and hot water pressure parts on power plants are covered by the Pressure Systems Safety Regulations 2000 (PSSR). To help interpret the requirements of the PSSR and understand the various defined roles and responsibilities, there is an associated Approved Code of Practice and guidance document (Ref. 1).

The objective of the PSSR is “to prevent serious injury from the hazard of stored energy, as a result of the failure of a pressure system or one of its component parts.” However, the guidance provided for achieving compliance is deliberately very general and non-specific, for example: “When deciding on the periodicity between examinations, the aim should be to ensure that sufficient examinations are carried out to identify at an early stage any deterioration or malfunction which is likely to affect the safe operation of the system. Different parts of the system may be examined at different intervals, depending on the risk associated with each part.”

This non-prescriptive, ‘goal-setting’ approach places the onus on the operator to do the right thing. In essence, to be compliant with the PSSR, due consideration should be given to all potential degradation mechanisms that could lead to component failure (and result in serious injury), ensuring that sufficient and proportionate inspections are completed to understand and mitigate the risks. Across steam and hot water pressure systems on a power plant, the range of active degradation mechanisms can be wide. For example, in a heat recovery steam generator that is used intensively, you might expect to encounter issues such as creep, thermal fatigue, creep fatigue, mechanical fatigue, Flow Accelerated Corrosion (FAC), corrosion and corrosion fatigue, amongst others. Looking further afield, legislation can vary significantly from one country to the next. Unlike the PSSR, there are cases where the nature and frequency of examinations is very prescriptive. Whilst prescriptive legislation may appear to be a safe, conservative approach on the face of it, there is the danger that not all potential threats, especially emergent issues, are addressed as part of the inspection plan.

For this reason, many operators outside the UK have chosen to adopt the general thrust of the PSSR, or parts of it, where this provides for a more robust and risk-based approach to pressure parts integrity management. Of course, by achieving compliance with the PSSR, not only is the primary issue of process safety being addressed – it also naturally follows that the owner can expect to see benefits in terms of improved plant reliability and availability.

IDENTIFYING THE RISKS

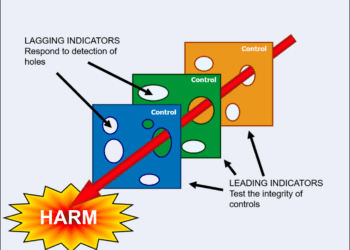

All relevant risks relating to pressure parts operation should be identified and an appropriate action plan put in place for maintenance and condition monitoring, e.g. visual inspection, non-destructive testing and analysis of plant data. Situations should be avoided where condition monitoring strategies only evolve in a reactive way, in response to failures and leaks, and where only the higher energy systems are addressed, i.e. creating ‘Cinderella’ systems that are overlooked, even though their failure could still represent a significant process safety risk and statutory noncompliance. A landmark example of this in the power industry is the terrible incident at the Mihama 3 nuclear plant in Japan in 2004, where the catastrophic rupture of a feed water pipe resulted in five fatalities. The degradation mechanism was FAC, which had caused in-service thinning of the pipe and, although the operating pressure of the pipe was relatively low (only 9 bar compared to 200 bar for some high pressure feed water lines), the large pipe diameter meant that the amount of stored energy was significant. As well as acting as a sobering reminder of the specific threat posed by FAC, this incident highlights the need to adopt a risk-based approach to the management of steam and hot water pressure systems, so that condition monitoring strategies encompass the risks from the whole plant.

RISK OWNERSHIP

“There is lack of clarity…over where responsibility lies, exacerbated by… fragmentation…and precluding robust ownership of accountability.” HRRBs are “complex systems where the actions of many different people can compromise the integrity of that system.”

A fully developed bowtie analysis can be used to illustrate, clearly and unambiguously, the safety-critical responsibilities of the parties involved in an HRRB project, including the client, designer, contractor, owner and operator/maintainer. By coming together to build a bowtie model for potentially significant risks, all parties can agree and understand their contribution to the case for safety, and appreciate the contribution made by others as well as any constraints and conflicts that may arise. Collaboration is encouraged and thinking in ‘silos’ is reduced.

Furthermore, a properly completed bowtie analysis provides reassurance to other stakeholders, not least residents, about the safety of their home and demonstrates who is responsible for what when it comes to managing risks.

CONCLUSION

Robust condition monitoring strategies that are risk-based provide the vehicle for achieving cost-effective regulatory compliance, managing process safety risk and increasing plant reliability and availability.

References:

1. Safety of pressure systems, Pressure Systems Safety Regulations 2000, Approved Code of Practice and Guidance on Regulations, UK HSE, L122, 2nd Edition, 2014.