Nuclear decommissioning demands new thinking

To achieve the stringent levels of safety required over their lifetime, nuclear power plants rely heavily on engineered safeguards. Other industries, where consequences are less severe, rely more on procedural controls and operator action to manage risks. Understandably, the emphasis has been on designing new operating facilities and upgrading existing facilities to meet improving standards.

However, as industries and countries around the world increase the focus on nuclear decommissioning and clean-up, significant challenges are emerging. There can be considerable political, regulatory and commercial pressure to make progress, yet it is vital that activities are carried out safely and risks are shown to be ALARP. In this respect, much of industry good practice has been developed for operating facilities, and may not be wholly applicable to the specific issues associated with decommissioning and clean-up. For example, the risk stays approximately constant for operating facilities, whereas there is often an increase during decommissioning and clean-up activities with a net reduction in the long-term.

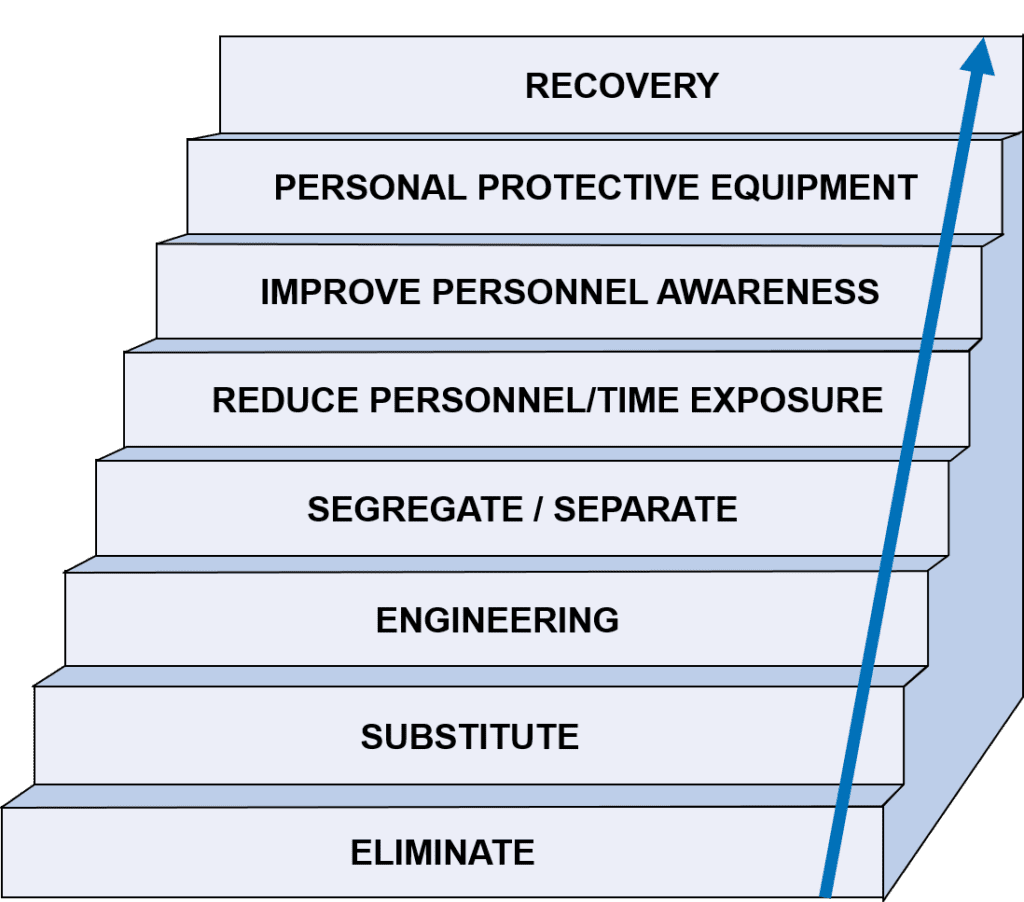

Figure 1 – Risk Control Hierarchy

In a typical risk control hierarchy [see Fig 1], engineered safeguards occur early in the order, and the capital outlay for these controls can be justified over the operating life of the facility. The situation is less clear cut for decommissioning. Whilst it is generally accepted that engineered controls provide greater safety assurance, other factors to consider include:

- The magnitude of unprotected consequences, which may be relatively low

- The required life of the control – one-off versus repeated activity

- The ease (or otherwise) of implementation and any interaction with the existing facility

- The time and effort required to design, build and commission new engineering

- Whether the ALARP principle can be satisfied through procedural control, perhaps supplemented by simpler engineered controls

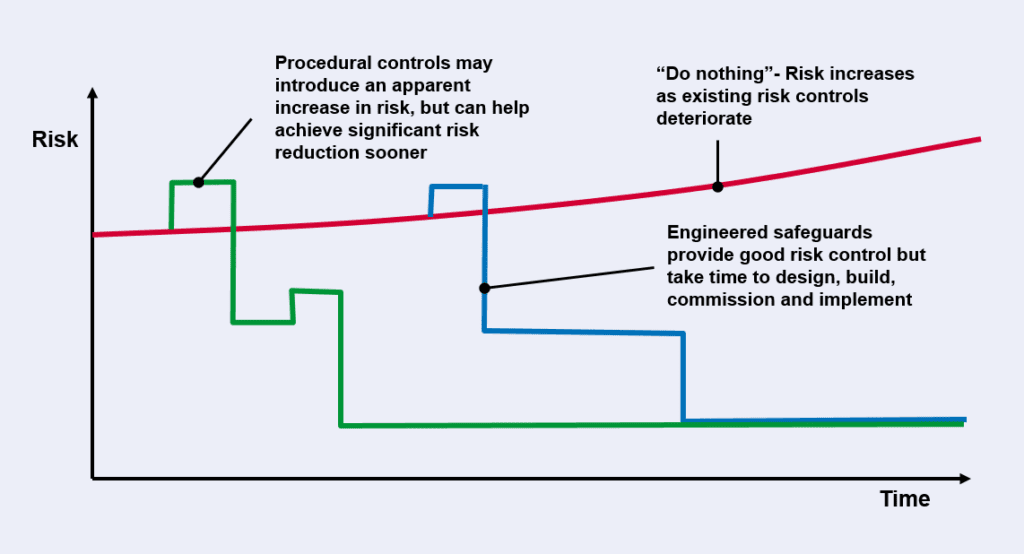

Figure 2 illustrates how there may well be overall risk benefit in making early progress with decommissioning/clean-up activities. In many instances ‘doing nothing’ invariably leads to an inexorable increase in risk as facilities and other risk controls age. A heavily engineered solution, which may only be required for a limited number of operations, takes time and effort to conceive, design, build, commission and implement.

Figure 2 – The Benefits of Earlier Decommissioning

Serious consideration should thus be given to the greater use of procedural controls to support safe undertaking of decommissioning and clean-up activities. Whilst a safety assessment may not give as much credit to procedural controls as engineered controls, the transitory increase in risk may well be justified in achieving overall risk reduction much earlier.

Procedural controls are not an easy option. It is a sobering reminder that many major incidents can be attributed to undertaking non-routine tasks (e.g. Chernobyl, Texas City, Kleen Energy) where a failure to adhere to procedural controls led to fatalities. It is imperative, therefore, that procedural controls are not simply recorded on paper, but are demonstrated in practice. This will mean thorough training for operational personnel and evidence that they have achieved a prescribed level of competency. Where possible, practical rehearsal of the activity in a non-hazardous environment should be carried out.

CONCLUSION

Decommissioning and clean-up present considerable challenges to all stakeholders. In many instances bespoke solutions to problems need to be developed, requiring ingenuity and expertise from a great many professionals. Conventional safety assessment and justification methods, which have invariably been developed for operating facilities, may well need to be re-evaluated and adapted to enable hazardous facilities to be safely and efficiently decommissioned.

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 17.