Wind of change: the risks & rewards of wind power

It is now widely accepted that global temperatures are increasing due to the increased emission of greenhouse gases trapping the sun’s heat in the Earth’s atmosphere.

In an effort to tackle this global warming, the Kyoto Protocol sets binding targets for industrialised countries to reduce greenhouse gases, with the UK agreeing to a 12.5% reduction from 1990 levels by 2012 [Ref 1].

In 2003, for example, electricity generation was directly responsible for a quarter of all UK greenhouse gas emissions [Ref 2]. As a result, the electricity industry is being targeted by the UK government in the drive to meet Kyoto targets. More specifically the Renewables Obligation, the UK Government’s mechanism to promote renewable energy development, requires licensed electricity suppliers to source a percentage of their electricity they supply from renewable sources – 9% for 2008/09 rising to 15%by 2015/16 [Ref 3].

WIND OF FORTUNE

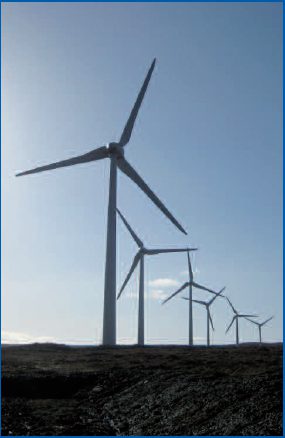

Whilst work continues in the development of other renewable energy technologies (wave, tidal, solar, geothermal, biomass etc.), wind power is perhaps the most immediately viable option in the UK due to the relatively simple, available technology, coupled with the country’s climate and geography.

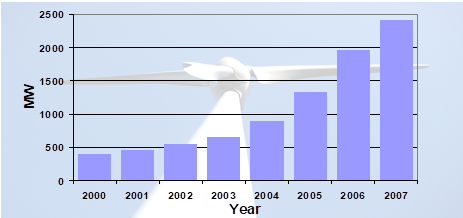

As a result, the UK has seen a rapid growth in the number of wind power generation schemes [see Fig 1], with this trend likely to continue into the future.

Figure 1 – The Growth of UK Wind Power Generating Capacity [Ref. 4]

HAZARDS OF WIND POWER

Planning applications for wind power developments and media coverage have tended to focus primarily on environmental issues, such as visual impact, noise, and the effect on wildlife. Yet, there are a number of other potentially significant hazards associated with the operation of wind turbines.

Failure of the turbine tower or its foundations could result in toppling, posing a risk to people and surrounding infrastructure. Failure of a turbine blade, due to a structural defect or turbine over speed for example, could cause all or part of the blade to be shed at high speed, potentially travelling large distances. Similarly, any ice formed on the blades could be shed as a result of an increase in wind speed or temperature.

The consequences of these hazards are largely dependent on the physical location of the turbine. A large wind farm on desolate moorland in rural Scotland, for instance, is likely to present a reduced risk compared with a single turbine in an urban setting.

This brings the relatively recent and growing trend of installing small scale turbines on schools, shops, houses etc. into sharp focus. Similarly, whilst the siting of large wind turbines on brown-field sites presents a number of undoubted advantages (e.g. land remediation, availability of grid connection and ease of access), the consequences of blade shedding or tower collapse may be considerable if they are located adjacent to populated buildings or industrial facilities with hazardous materials or processes.

Accessing wind turbines to complete maintenance or repairs also presents its own hazards. With the majority of electromechanical equipment located anything up to 100m above ground level there is an obvious risk of a fall from height. Accessing offshore wind turbines by boat poses additional challenges, especially if the weather worsens.

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

The worst case consequences of wind power hazards are much less severe than those associated with other industries such as nuclear power, oil & gas and rail transport.

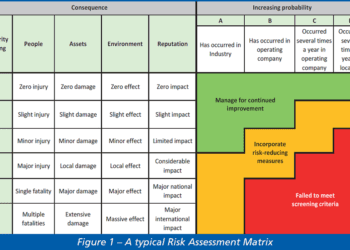

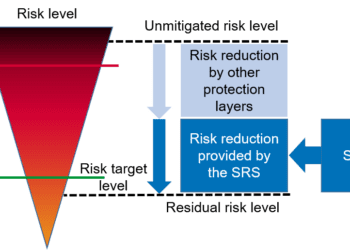

Nevertheless, the wind power industry has the opportunity to read across and adapt relevant risk assessment and management techniques and processes in order to demonstrably control any significant hazards.

Until this is achieved, the wind power industry remains exposed to the risk of a major incident, which could dramatically affect public opinion and limit future development, at least in the short term.

References

1. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [www.defra.gov.uk]

2. UK Statistics Authority [www.statistics.gov.uk]

3. Department for Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform [www.berr.gov.uk/energy/sources/ renewables]

4. British Wind Energy Association [www.bwea.com]

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 14.