Cyber-space – Emerging issues and solutions in the cyber-security of operational technology

The risk to facilities arising from the cyber threat to industrial automation and control systems – Operational Technology (OT) – continues to attract more attention. But it should not be assessed in isolation. There is a need for a holistic approach to security that recognises the complementary nature of safety and security outcomes and highlights issues and potential fixes in the challenging area of cyber-security.

Let us first consider why cyber-security is becoming such a hot-topic. With increasing emphasis by regulators, governments and international security organisations, it is clear that risks to cyber-security of OT are being taken seriously. As the world moves to a future where computer controlled industrial systems are embraced, this opens up organisations to a greater variety of risks. A clear understanding of, and easy access to, cyber-security risk information is required. Coupled with an increasingly aware public, the potential for major reputational damage means organisations cannot afford to ignore the very real risks introduced by the computerisation of industrial systems.

COMPLEMENTARY OUTCOMES

An understanding of this OT world starts by recognising there is an overlap between safety and security. The required outcomes are complementary, but they can be used to support each other.

Safety protects against unintended events that are hazardous to life and the environment. Security protects against deliberate, malicious acts targeted at creating damage to equipment, process or life, depending on the goal of the threat actor. Collectively, they aim to protect what is important to society and the business.

Notably, for a system to be truly safe, it must also be secure.

IT / OT – WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

The boundary between Information Technology (IT) and OT is becoming increasingly blurred. As more IT based technologies are introduced into the OT space, care must be taken to define their boundaries, recognising their potential effect (or absence of effect) on safety and cybersecurity.

The definitions of these spaces are individual to each organisation. The two statements below offer a simplistic view of the IT/OT divide, but it is a starting point for further consideration, and offers a guide for organisations in creating their own definitions.

- If it goes wrong and it causes no direct real world physical consequence or no impact on industrial or essential infrastructure services, then it is likely IT.

- If it goes wrong and the consequences could be physically catastrophic to either individuals or wider society, then it is likely OT.

HOLISITIC SECURITY

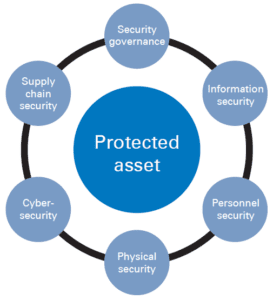

Increasingly, organisations need to look at security in a holistic way when it comes to protecting their assets. Figure 1 shows the six domains of security, each of which is important to consider when protecting any asset. These domains should no longer be seen as separate layers, but as interconnected elements of security.

The goals and level of rigour applied to each domain will depend on a range of factors such as business goals, the threat environment the asset operates in and the level of resources available to invest in security.

THE ISSUES WE FACE

Many organisations are struggling with the security of their OT and it is not always clear to them where to start. Guidance around cyber-security is frequently skewed to the tactical fix rather than an overall approach to security.

In the past, the need for physical access to, and specialised knowledge of, OT provided some degree of security. Today, the connected, information-driven world we now live in has eroded that protection.

Cost is frequently seen as a large barrier to effective security risk management, with organisations often feeling that financial resources are better spent on products sold to fix tactical cyber-issues. This often leads to decisions being made based on incomplete risk information.

The commonly established cyber-security techniques that organisations rely on for their IT systems do not directly correlate to the objectives and requirements of the OT systems they operate. This can result in security controls that do not effectively perform their function in the OT environment.

The consequences of cyber-attack can be drastically different between IT and OT, and may not be fully appreciated by IT based cyber-security teams. This may lead to misunderstanding of the types of controls needed, the impacts of introducing certain controls and how these should be evaluated.

The cyber community itself has also created its own problems. As an industry, the language that is used is very specific to the discipline. Different approaches are used and, unlike the safety domain where information on accidents is widely shared (in many cases as a regulatory requirement), secrecy is common when it comes to security incidents, thereby missing out on the benefits of learning from shared knowledge.

Cyber-security organisations produce products and sell these as solutions to all cyber-ills and, whilst this is an attractive idea, it is unfortunately flawed. Tactical fixes are very unlikely to solve the overall security risk problem, or be cost-effective in the long-term.

LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL

While this outlook sounds gloomy, there is hope.

Cyber-security consultants can start to match the language they use to the client’s environment, ensuring that definitions are consistent and security concepts are introduced in an understandable way.

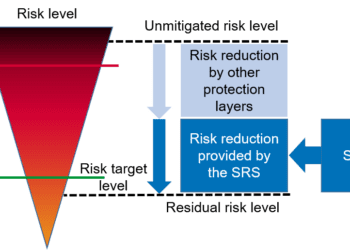

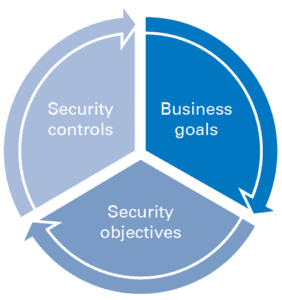

As Figure 2 illustrates, understanding the most important business goals and translating those to pragmatic security objectives, and then ensuring that the risk assessment outputs and control recommendations are supportive of those objectives, helps to properly target security controls.

Arguably the best way to achieve effective cyber-security is to use processes such as HAZOP and LOPA style studies, building on their success in the safety industry. Cyber-specific HAZOP and LOPA activities can be a very time- and cost-efficient way to assess cyber risk, and are already familiar to the high hazard industrial sectors.

As the discipline moves forward into the future, the most important thing that can be done within the cyber-security space is to learn from other disciplines such as engineering, safety and human factors. Finding and adapting the best techniques from other well-established disciplines will help to guide us to more effective security risk management.

CONCLUSION

The world we live in is at the mercy of rising cyber-security threats. As more connected and computerised technology is introduced into industrial facilities, identifying appropriate controls, measuring their success and understanding their weaknesses, is vital for organisations.

The cyber-security domain needs to look at the engineering and safety worlds to develop holistic approaches and methods to bring cost-effective, impactful security risk management to as many organisations as possible.

This article first appeared in RISKworld 41, issued April 2022.