Proportionality – the role of safety management in climate action

The recently popularised term “Anthropocene” alludes to the impact of human life and endeavour upon the geology and ecosystems of our planet. As the dawn of this new geological epoch breaks upon the Earth, worldwide awareness is steadily rising of the harsh realities of climate change. Encouragingly, viable technologies are now emerging with the potential to reduce emissions and sequestrate atmospheric carbon dioxide.

NEW TECHNOLOGIES, NEW HAZARDS

Effective climate action will require an ambitious expansion of new and existing technologies, including (for example) renewable energy generation, electric vehicles, smart energy management, carbon capture and storage, and a hydrogen economy as a substitute for natural gas. These bring hazards such as:

- Impacts from wind turbine blade failures.

- High energy battery fires and explosions.

- Asphyxiation from gross releases of carbon dioxide.

- Hydrogen fires and explosions.

Emerging technologies have suffered disastrous setbacks in the past, where a rush to market resulted in loss of life. In the post-war race to commercialise jet airliners, for instance, the de Havilland Comet captured the public’s imagination and looked set to corner the airline market. However, within two years of entering service, five aircraft suffered highly publicised accidents. Two were caused by unexpected stall characteristics during take-off, and three involved catastrophic in-flight break-ups. The catastrophic failures were later attributed to metal fatigue from cyclic loading, which was not fully understood at the time, aggravated by stress concentrations and the riveting method. Sales never recovered and within ten years Boeing emerged as the leading supplier of commercial aircraft by an overwhelming margin.

EXCESSIVE SAFETY?

We live in different times now; times in which we are more cautious and more aware of the importance of safety, both of itself and of its impact on reputation. Our safety assessment processes and tools are manifold and tried and tested.

Inevitably, there is a temptation to impose higher standards of safety and regulation on new technologies, compared to those that they replace. Raising the bar in this way risks stalling the introduction and proliferation of solutions that could quite literally save the planet. With new technology, there is the opportunity to get the balance right from the start, without setting a precedent that could be difficult to overturn.

There is an interesting parallel here with the UK nuclear industry ten years ago. More and more it was becoming clear that the exacting nuclear safety case regime (and its regulation) was delaying or even preventing the decommissioning of nuclear facilities, not least because of the cost and effort required. In other words, the same standards and expectations were being applied to decommissioning hazards as were originally intended to prevent a catastrophic reactor core meltdown. As a result, the industry has re-invented itself to arrive at decommissioning safety cases that are proportionate to the risk and recognise the safety benefit of getting the job done.

ACHIEVING BALANCE

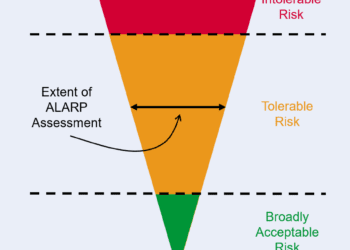

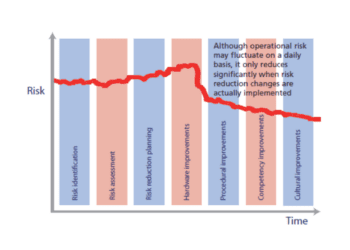

For safety professionals, the desire to achieve continuous improvement must go hand in hand with an awareness and determination to avoid excessive intervention. Key to this will always be a disciplined application of risk acceptance criteria – including the requirement to reduce risks As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP) – with a holistic consideration of the broader context in which our new technologies for climate change must function.

A good example is the developing UK wind power industry. Consider for a few moments the prospect of building and operating a wind turbine adjacent to a school, or a gas storage depot, or a nuclear power plant. To assess and manage these and other hazards many of the leading operators in the wind industry apply a cost-effective safety case style framework, which expends effort according to risk.

Get this approach wrong, of course, and a single accident can change the regulatory landscape – for example, the Piper Alpha disaster

in 1988 completely transformed the safety requirements for the UK offshore industry.

There is clearly a balance to strike between what might be entirely proportionate and reasonable measures to bring to bear upon an emerging high-technology industry, and the otherwise over-bearing and costly burden of excessive ‘paper safety’ that could ultimately risk the success and very survival of a new technology before it can secure its place in history.

CONCLUSION

By playing our part in assuring the safety of new technologies for climate action, we also have a duty to take a proportionate approach that weighs novelty against both risk and the long-term goal of saving the world.

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 35