Boom or bust – the impact of low oil prices on process safety

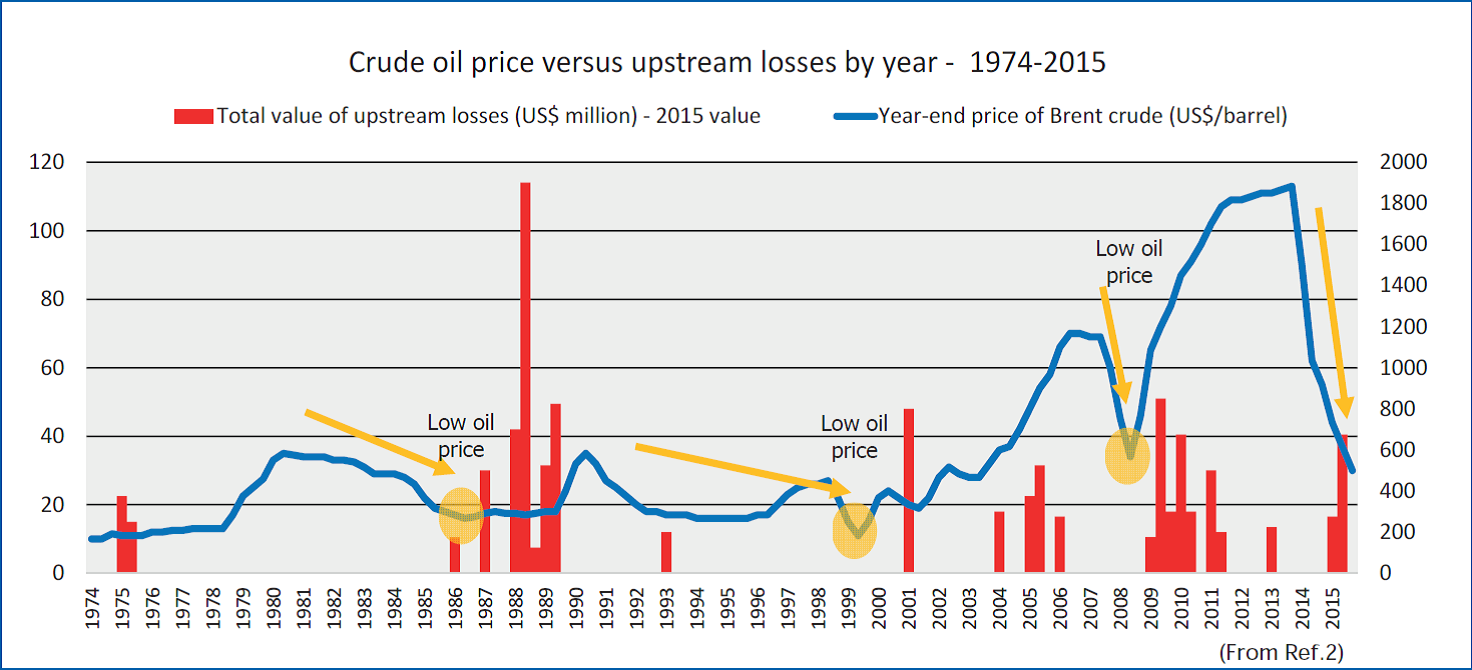

“We know from past experience how low oil prices impact upon business thinking about process safety – and it’s not good”. That’s how Judith Hackitt, the chair of the UK’s health and safety regulator, described the impact of a low oil price on process safety in early 2015 (Ref.1). A recent report from Marsh (Ref. 2) would appear to support Hackitt’s claim, with a telling graphic showing the historical occurences of major losses compared with the oil price (see above).

LOSSES FOLLOW OIL PRICE DECLINES

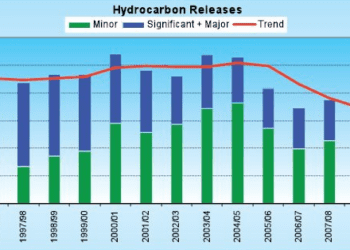

The last 18 months have not been the first time the oil industry has seen falls in the price of crude oil. Significant reductions in the crude oil price also occurred between 1980 and 1986, in the late 1990s and again in 2008. Looking at the distribution of upstream losses, we can see that there was a significant increase in large losses in the years that followed each of these periods.

CAUSATION OR COINCIDENCE?

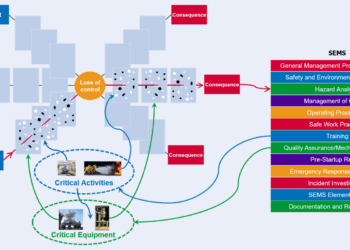

The Marsh report rightly points out that “correlation does not mean causation: the fact that a relationship is observed between two variables does not always mean there is a direct linkage between them.” The report further emphasises that “the cause of every major loss is a combination of a unique and complex interaction of faults and failures of hardware systems, management systems, human error, and/or emergency procedures.”

Yet there are fundamental reasons why a declining and low oil price could adversely impact process safety, and why causation is more probable than coincidence. Lower prices inevitably lead to cost-saving initiatives that can compromise asset integrity, such as:

- A reduction in maintenance and inspection of engineered systems.

- A reduction in manpower leading to lower morale, fatigue and a tendency to cut corners.

- Organisational changes culminating in a loss of expertise and corporate memory, with an increased chance that less experienced personnel will make a serious mistake.

- Reduced training that fails to maintain competencies of workers.

- A decline in investment in new equipment, placing a greater reliance on existing and possibly antiquated systems.

- Hasty decision making to improve efficiency, maintain production and reduce unplanned downtime, without considering all the process safety implications.

PROCESS SAFETY LEADERSHIP

So what can be done? Although the oil price has fallen, the standards required to protect workers’ lives have not changed. And we all know the cost of major accidents – BP recently revised the total cost to its business of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster to a staggering US$61.6 billion. The bottom line is that leaders need to step up to ensure that the right decisions are made so that asset integrity does not suffer. Areas requiring specific attention include:

1. Chronic unease: There should be a heightened sense of vulnerability amongst all leaders – from supervisors to senior management. Everything cannot be assumed to be well and decisions should not be assumed to address process safety.

2. Risk assessment: All decisions impacting asset integrity should be thoroughly risk assessed by competent people, whether organisational, engineering or procedural changes.

3. Performance monitoring: A great deal of effort in recent years has been put into implementing process safety performance indicators. These should be scrutinised diligently, especially those leading indicators which act as precursors of loss events, to detect any signs of adverse trends, e.g. near misses, leaks, maintenance backlog.

CONCLUSION

Periods of declining and low oil prices since the 1970s have been followed by spikes in upstream losses. Will the industry buck the trend this time or is it already too late? Have decisions already been taken that mean that large losses are inevitable? Or has the industry learnt enough lessons that this time it will be different? We really hope so.

References

1. Judith Hackitt, HSE Chair, Process Safety Summit II, January 2015.

2. The 100 Largest Losses, 1974-2015, Marsh, March 2016.

This article first appeared in RISKworld issue 30